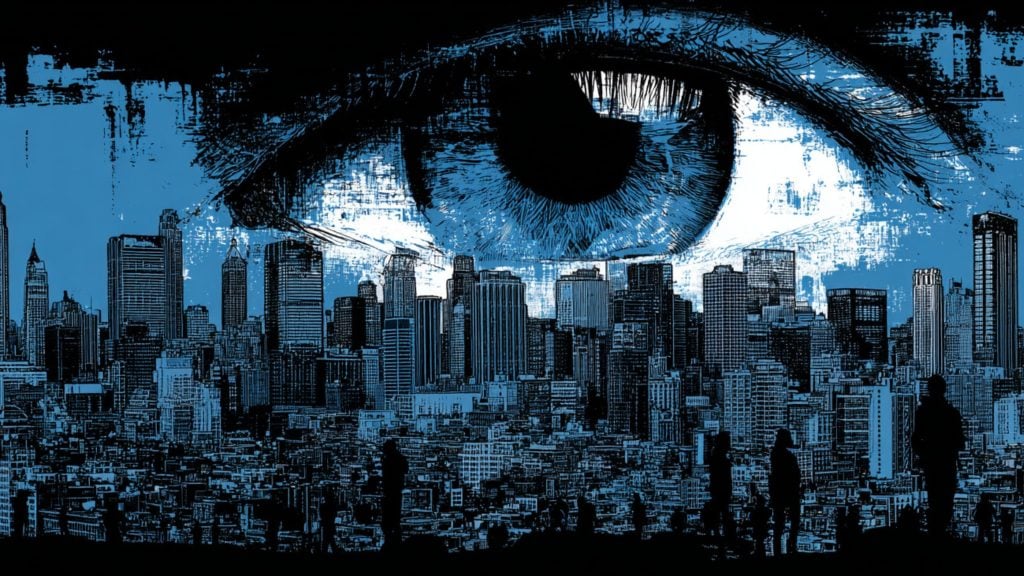

Bluesky, the social platform once meant to be a sanctuary for free expression, has started bending to government demands. Despite a loophole that still allows some users to slip through the cracks, the network’s decision to censor at the behest of Turkish authorities has ignited concerns about whether its foundation is as anti-censorship as promised.

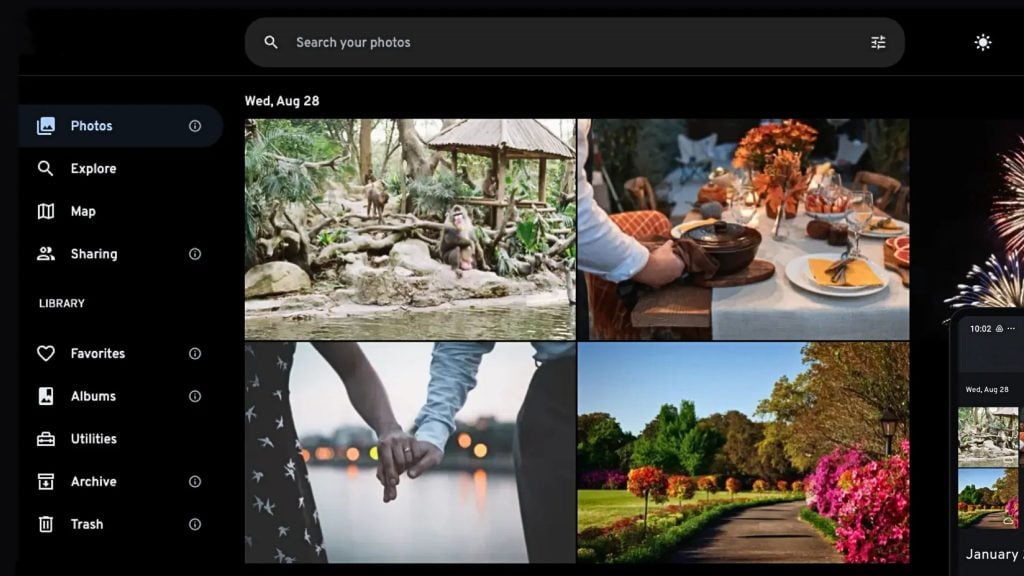

A report recently disclosed that Bluesky agreed to restrict 72 accounts in Turkey. Now, users in the country are cut off from these voices. Out of those, 59 accounts were censored under claims of protecting “national security and public order,” while an additional 13 accounts, along with at least one post, were hidden from view.

For a platform that attracted many Turks escaping the heavy-handed censorship elsewhere, Bluesky’s move to comply with Turkish government pressure feels like a betrayal. Users are now questioning whether the platform’s promises of openness were ever genuine.

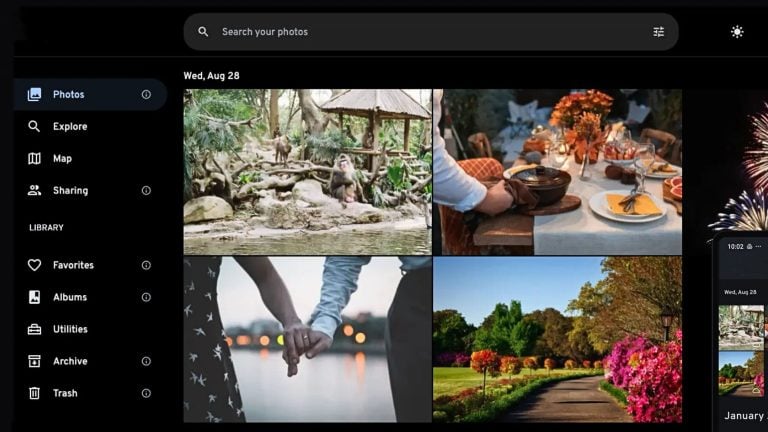

The issue is Bluesky’s official app, which offers some user-level moderation settings but does not permit opting out of the company’s centralized censorship system. A significant part of that system involves geographic labelers, including a recently deployed Turkish-specific one that automatically hides targeted content inside the country.

If you’re using Bluesky’s official app and the company decides to block content based on your location, you are stuck. There is no official way to view the censored accounts or posts.

More: EU Censors Set Their Sights on Bluesky

Nevertheless, the architecture underlying Bluesky offers an escape hatch — at least for now. Built on the AT Protocol, Bluesky supports a network of third-party apps, collectively called the Atmosphere, where moderation can be handled differently or even ignored.

Because the censorship is applied at the client level through geographic labelers, and because the restricted accounts are not banned from Bluesky’s actual servers and relays, independent apps can still access them. Apps like Skeets, Ouranos, Deer.social, and Skywalker, which have not adopted geographic moderation labelers, provide ways for users in Turkey to reach content the official app blocks.

However, this workaround is fragile.

Most third-party developers have not intentionally resisted censorship. Rather, adding geographic labelers would require extra coding, and with their apps flying under the radar thanks to smaller user bases, developers see little immediate reason to comply.

But if any of these apps were to grow large enough, they could easily become targets for government pressure — or risk being delisted from app stores like Apple’s if they refuse to enforce censorship demands.