China plans to award media accreditation depending on a journalist’s social media history. The move will discourage reporters from posting criticism of the Chinese Communist Party online, further restricting independent journalism in a country where people do not trust the state-run press.

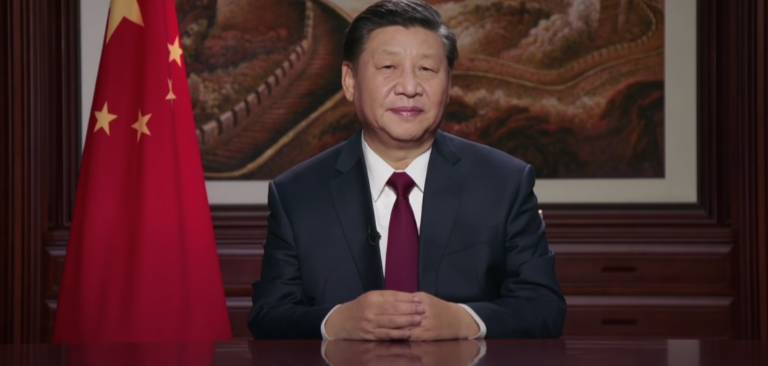

On January 19, the Chinese government announced that it would be looking at social media history before awarding media accreditation. It justified the decision by saying the purpose of the new regulation is “to thoroughly implement General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important ideas on propaganda and ideological work and build a team of journalists who are politically strong, realistic, and innovative.”

The new rule will affect radio, television, print, and website-only news outlets. Employing a reporter without a valid media accreditation will attract harsh penalties. The rule will not distinguish between professional and personal statements.

The change is a major blow to the already restricted independent journalism in China. Some news outlets and journalists publish content that is not approved by the censorship authorities on social media and now even this will be under threat.

The new rule will also affect citizen journalists. If it were not for the citizen journalists who recorded images and footage from their phones, the chaotic government’s actions at the beginning of the pandemic would have remained under wraps.

The new rule will require citizen journalists to acquire press accreditation.

Some of the citizen journalists who covered the situation in Wuhan at the initial stages of the pandemic have already faced harsh consequences.

Zhang Zhan was detained and later charged and slapped with a four-year sentence. Another two are under home arrest, while the whereabouts of another one, Fang Bin, are unknown.

The ruling Chinese Communist Party has increased its distaste for criticism since Xi Jingpin took office. Authorities have become more harsh on people using banned social media platforms, like Facebook and Twitter, to criticize the CCP.

Over the past three years alone, at least 50 people have been arrested and sentenced for using banned platforms to criticize the government for issues such as Uighur re-education camps, Taiwan’s independence, and the government passing laws to reduce freedoms in the autonomous city of Hong Kong.

After the new press accreditation rule takes effect, there will be significantly fewer stories critical of the CCP, meaning more freedom for the regime to spread its propaganda.