Uyghur-language websites are now almost non-existent, including Bagdax, a news website that followed the strict censorship rules and had about 100,000 users.

In 2016, Bagdax’s owner, Ekpar Asat, and a million other Uyghur minorities, was caught up in a mass detention campaign. A year after that raid, most Uyghur websites stopped posting updates.

The people behind those websites, including IT experts, developers, and computer scientists, are in the detention camp system, WIRED reported. Beijing claims that the camps are centers for reeducation, countering extremism, and vocational job training. Human rights groups claim the camps are about wiping the culture of the Uygurs, most of whom are Muslim.

Rayhan Asat, Ekpar’s sister, said that shutting down these websites is attacking their language and culture and that Beijing often targets the best and brightest in the Xinjiang region.

“Why would an eminent tech entrepreneur need to be reeducated? What kind of skills does he need?” she asked.

In 2014, Urumqi, the region’s capital, had a few companies that had started to blossom. But the success did not last long because Beijing intensified its crackdown on “extremism” in 2016.

“Our region literally became a prison without walls,” says Abdurrahim Devlet, the founder of Bilkan, a company that had developed 30 apps, an Uyghur online bookstore, and a hardware line. After a wave of arrests, including Bilkan’s manager, Devlet shut down his company and is now living in Turkey.

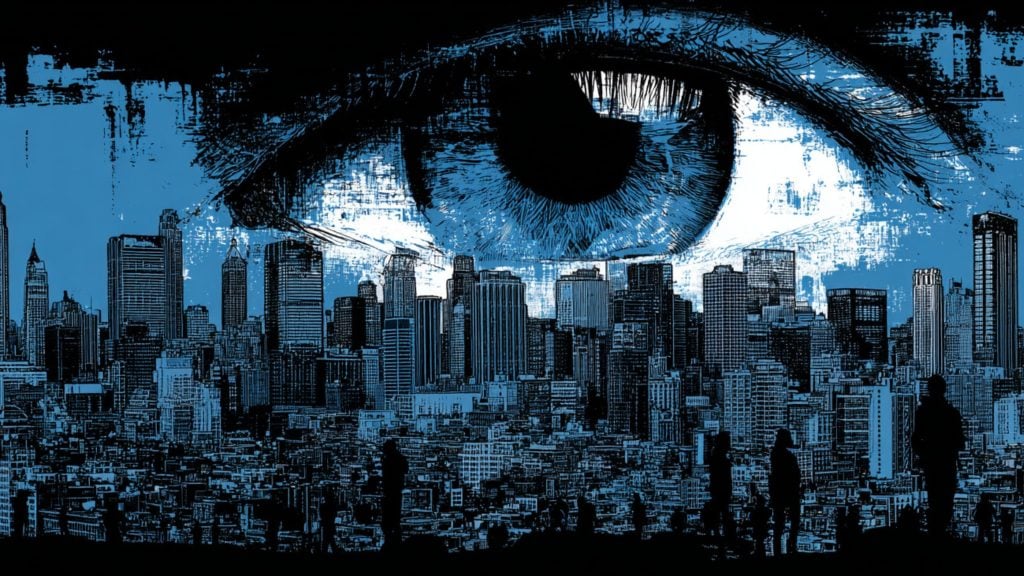

To discourage Uyghurs from creating websites and other online tools, the government has also blacklisted Stack Overflow and GitHub, popular web development resources that are still accessible in the rest of China.

“It’s like erasing the life work of thousands and thousands of people to build something—a future for their own society,” says Darren Byler, assistant professor of international studies at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver to Wired. He has also written several books on how China treats Uyghurs. “That’s just been eliminated overnight, and there’s not much of a way of recovering that information.”

Those websites were places where Uyghurs could discuss controversial issues and learn about their cultural and Islamic practices. According to Philadelphia’s Drexel University’s associate professor Rebecca Clothey, those websites were also a place they could show the world who they really are outside the narrative provided by Beijing.

“An online space in which they can talk about issues that are relevant to them gives them the ability to have a way of thinking about themselves as a unified mass,” she said. “Without that, they’re scattered.”

Now they are forced to use Chinese apps. But they have found creative ways to communicate like holding up signs with messages when making video calls and chatting through gaming apps. They have also been stealthily filming their life in Xinjiang and posting the clips on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok. Some have captured people being loaded onto buses, filmed orphanages where the kids of detained Uyghurs are taken, or even filmed themselves crying over a photo of a loved one. The clips do not contain any hashtag or text.