When the bell rings across India’s medical colleges on May 1, signaling a new day of lectures, dissections, and rounds, a new kind of observer will quietly take its place at the front of every classroom. Unlike students, it won’t scribble notes or ask questions. This observer doesn’t blink, doesn’t forget, and most importantly, doesn’t trust.

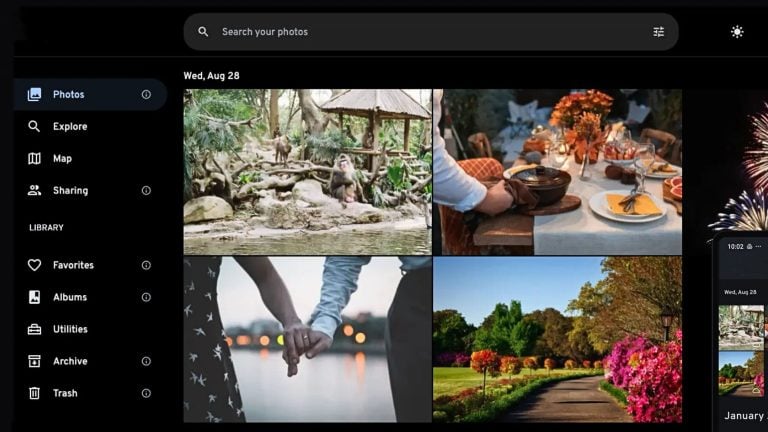

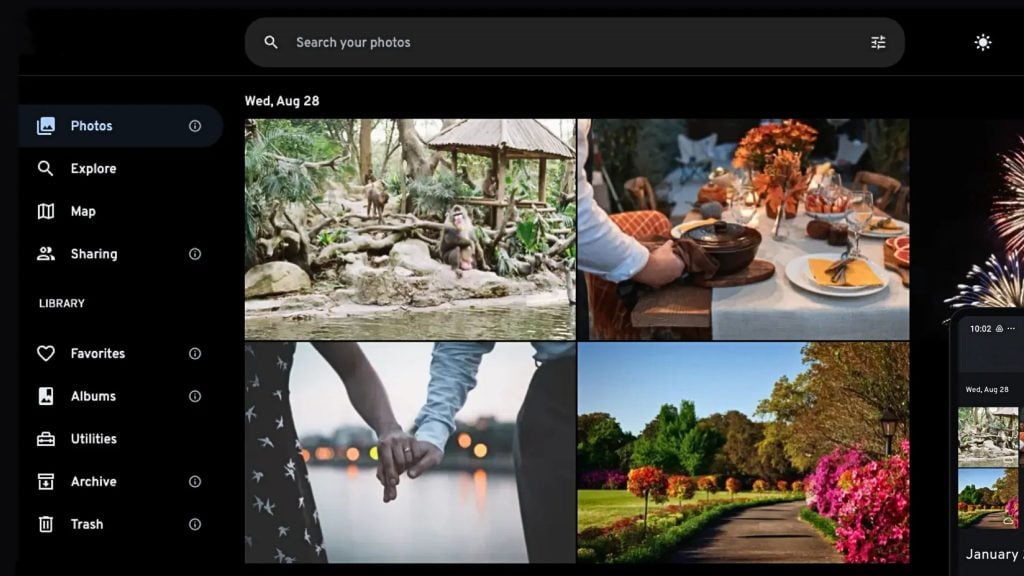

It’s the latest mandate from the National Medical Commission (NMC): a facial recognition system (FRS) tethered to GPS location tracking, rolled out to ensure faculty attendance is logged down to the exact time and place. But this isn’t just about headcounts. It’s about who gets to watch, who must comply, and what happens when trust is supplanted by tracking.

To the NMC, this shift is a stride toward modernization. The old Aadhaar-linked fingerprint systems, clunky and prone to manipulation, are being phased out in favor of tech that promises seamless integration and real-time oversight. However, for faculty across India, the message lands differently.

“Forcing faculty members to share their real-time location is not only unjustified but also offensive,” wrote the Medical Teachers Association of Bundelkhand Medical College in a letter dated April 19. “We are professionals, not subjects of suspicion… The NMC is not a moral policing agency.”

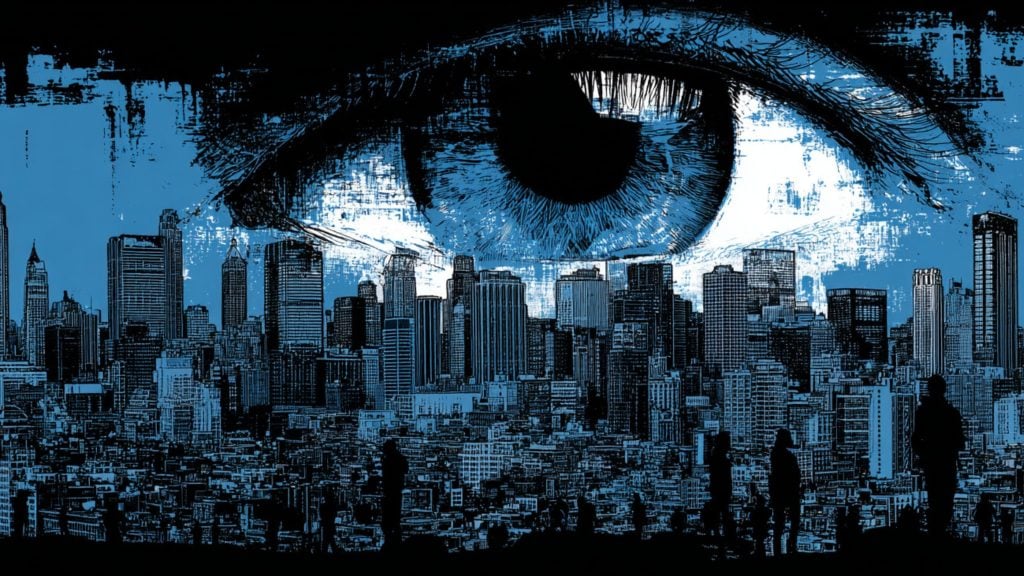

Their frustration is echoed widely. The concern isn’t about adapting to technology. It’s about the kind of power that technology now wields. GPS tracking doesn’t just confirm your presence; it charts your movement, stores your routines, and gradually reshapes what privacy means inside a workplace.

Dr. Sarvesh Jain, president of the association, made the stakes crystal clear in his remarks to EdexLive. “If everyone is right, then Pegasus should be installed on all our devices. This is not about right or wrong, it’s about privacy, which is a Constitutional right. I may have ‘n’ number of secrets, and as long as I’m within the law, they’re my business.”

For educators like Jain, this isn’t about hiding wrongdoing. It’s about resisting a creeping presumption of guilt that now comes with every login and swipe.

To understand the undertow here, it helps to rewind a few years. Until 2020, medical education in India was overseen by the Medical Council of India (MCI), a somewhat unruly but independent body. In a sweeping reform aimed at rooting out inefficiencies and corruption, the MCI was dissolved, and the National Medical Commission took its place.

The change, though administrative on paper, was more than just structural. “Earlier, we had the Medical Council of India, which was independent. Today, NMC is a body formed and appointed by the government, and is now acting like a surveillance agency,” said Jain.

It’s a sentiment that gets at the heart of the disquiet. The shift to NMC has been accompanied by an unmistakable centralization of control. Regulation, once a system of peer review and academic standards, increasingly feels like a mechanism of enforcement. The classroom, once governed by collegiality and discretion, is beginning to resemble a monitored space.

Not everyone sees the FRS mandate as a step too far. Supporters argue that something had to give. The MSc Medicine Association (TMMA), for example, believes the system is overdue. Their defense hinges on an uncomfortable truth: ghost faculty and fake attendance records have plagued Indian medical institutions for years.