EU Parliament’s and EU Council’s proposal to introduce new surveillance rules, known as “chat control,” was first introduced in 2022, but has faced many hurdles and is yet to be adopted.

The attempt to push through the legislation last failed in July – but it is now back. Officially designed to prevent and prosecute child sexual abuse online, critics say will result in automated mass surveillance via scanning of all private communications and represents yet another attempt to compromise encryption.

On August 28, the EU Council site announced that it had put the “chat control” proposal back on the agenda for the member countries’ governments to debate; however, they will resume work on September 4 on a document that is secret.

“Not accessible” is how the site describes the content of the document – even though, a request for access can be submitted. It is not clear what conditions such a request would have to meet to be granted.

While citizens in EU countries are currently left in the dark as to what the proposal contains, and how it might affect their privacy (but also security, because of the encryption component), it is worth looking back at what previous attempts to adopt the “chat control” proposal contained.

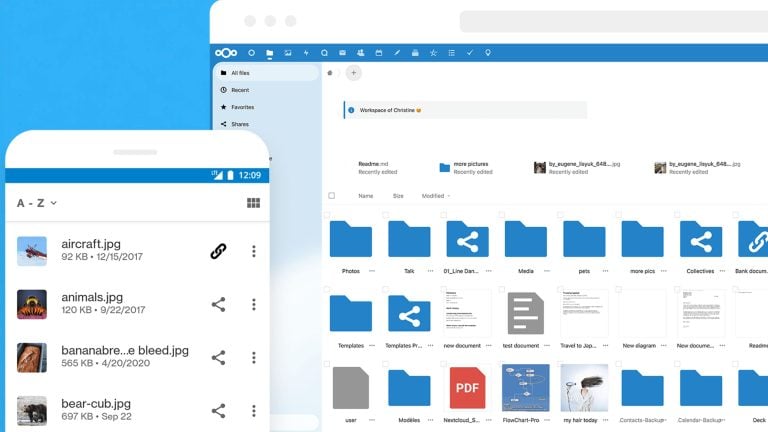

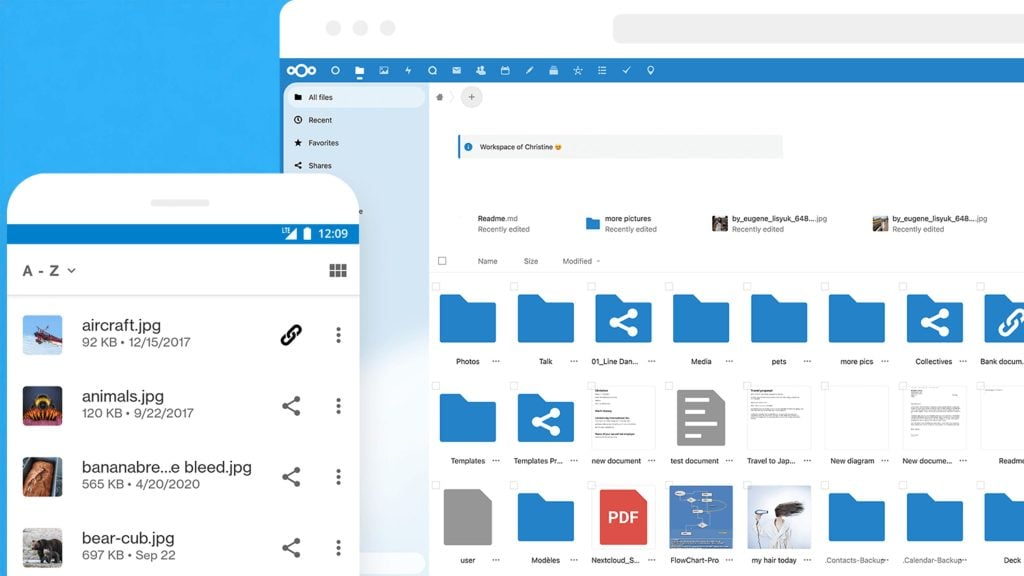

Long-time opponent and member of the European Parliament (MEP) from Germany Patrick Breyer previously explained that the new rules would introduce automated searches and disclosure of private chats (end-to-end encrypted ones as well), as law enforcement looks for illegal photo and video content in those communications.

This sweeping, blanket approach to surveillance, where the fact that the automation tools are prone to errors is not the least of the concerns, cannot be refused by users – rather, it can, but will result in those users getting “blocked from receiving or sending images, videos, and URLs,” Breyer wrote in June.

At that time, close to 50 politicians from a handful of EU’s 27 member countries raised their voices against adopting the latest proposal (which a month later failed), warning that since introducing mass surveillance of this type is in contravention with EU’s fundamental rights, it would also likely be rejected by courts.

“Do you really want Europe to become the world leader in bugging our smartphones and requiring blanket surveillance of the chats of millions of law-abiding Europeans?” Breyer asked at the time.