This week’s launch of the UK National Health Service (NHS) coronavirus contact tracing app has raised fresh concerns and complaints about the app and the associated contact tracing law’s impact on civil liberties and privacy.

The nationwide launch of the app follows the introduction of a new UK contact tracing law last week that requires businesses to display government-issued QR codes and refuse entry to customers unless they either download the UK National Health Service (NHS) contract tracing app and scan these QR codes upon entry or hand over personal information.

Ever since the app was announced, it has been mired by concerns over how data is handled, the restrictions it imposes on citizens, and the legality of the associated Test and Trace program which the government previously admitted was operating illegally after it was revealed that the program had failed to perform legally required data protection checks.

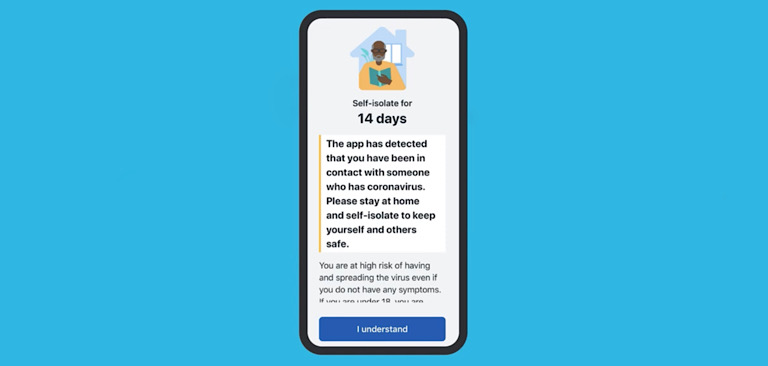

And one of the top concerns that has arisen with the launch of the new app is that it could be wrongly telling 30% of users to comply with government imposed self-isolation restrictions when they haven’t come into close contact with an infected person.

Because the app relies on Bluetooth signals which can be affected by nearby objects, the app can falsely determine that a person has come close to an infected person when they were actually just close to a Bluetooth emitting object.

The app is supposed to send a notification telling people to self-isolate for two weeks when it determines a person has come within 2 meters of an infected person for 15 minutes over the course of a day. But false positives have been triggered on people who are up to 4 meters away from an infected person. The government claims that 4 meter false positives are rare and most of the false positives are on distances of between 2.1 meters and 2.2 meters.

In addition to the false positives issue, the privacy groups Big Brother Watch and Open Rights Group have also warned that there will be a “dire public health consequence of ignoring test and trace privacy concerns.”

The groups have instructed the data rights agency AWO to send a legal letter demanding that the UK government provide information on how it will secure the data it collects under this new contact tracing law.

The letter also asks the government to confirm whether it has conducted a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) for the Test and Trace program as a whole.

Jim Killock, the Executive Director of Open Rights Group, criticized the government’s previous failure to conduct these data protection checks.

“No one knows what will happen if things goes wrong and this Government doesn’t seem to have thought this through,” Killock said. “This Government has had 6 months to fix the test and trace programme and on the eve of the launch of this App one thing is for certain; this Government is flying by the seat of its pants.”

Silkie Carlo, Director of Big Brother Watch, raised concerns over how the program could lead to mass recording of UK citizens’ movements and blasted the government for imposing restrictions on people that want to enter certain business premises:

“The Government’s new approach to contact tracing is no longer based on public trust, but on exclusion, criminal sanctions and police enforcement. Many people will be rightly shocked to find they’re refused entry to coffee shops and restaurants unless they use the NHSX App or hand over their personal contact details.”

She added that the new law is “draconian,” “excessive,” and that it “poses a serious risk to privacy and data rights.”

Yet these ongoing concerns have done little to dissuade the UK government from proposing further digital tracking measures.

Coronavirus passports that give people a “passport to mingle with everybody else who is similarly not infections” and a digital ID system that feeds into user data from the web have both been suggested by high ranking government officials this month.