It’s always upsetting to see headlines about an online service getting breached. Sure, by this point, most of us realize that there’s no such thing as perfect security. That it’s a constant cat and mouse game. Most companies employ all sorts of non-tech-savvy folks that may not always abide by best practices. And of course, security is as strong as the weakest link.

When it comes to services focused on privacy, however, it’s particularly unforgivable. Their entire product relies, very directly, on being able to protect their users’ privacy. So when an app that advertised itself as an end-to-end encrypted solution for communicating during protests ends up being riddled with security flaws, public backlash is perfectly justified.

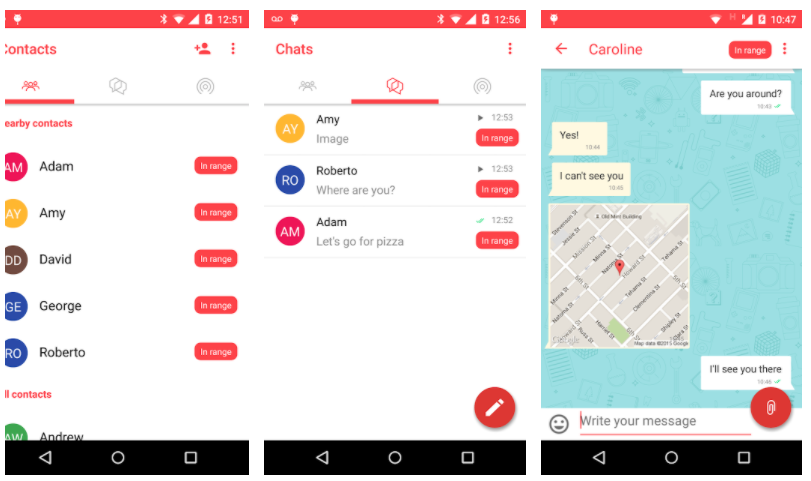

That is the story of Bridgefy, the app that quickly took by storm the world’s populations that are the least satisfied with their respective governments. Places like Lebanon, Iran, Zimbabwe, India, Hong Kong, and even the US have seen a strong surge in Bridgefy downloads lately given the coinciding uptick of protests going on in those regions.

Initially, Bridgefy advertised itself as a way for people to communicate offline using Bluetooth, for cases when internet connectivity isn’t available like natural disasters, concerts, and sporting events. For obvious reasons, protesters ended up finding an alternative use for it. But rather than Bridgefy warning those users that their solution isn’t safe enough for that use-case, they completely leaned into it. Bridgefy began advertising themselves proudly as “The Protest App”.

The key difference between protests and other examples of large gatherings like the ones mentioned above, is that in the context of protests, it’s not only unsurprising but even expected to have someone trying to hack your users. It would be rather strange for someone to hack into a natural disaster rescue operation, but not at all strange for authoritarian governments or even counter-protesters to try and identify protesters or intercept their communications.

Back in April, a group of security researchers discovered several major flaws in Bridgefy’s system. These flaws allowed for deanonymizing users, decrypting and reading private messages, tampering with messages, and even impersonating other users.

All of this is possible due to the fact that Bridgefy sends the user’s identity over plaintext, without any form of encryption. This is that “metadata” that you often hear about not being encrypted – only in this case, the metadata includes some very critical information. Attackers can not only use this to identify users, but even impersonate them, receive messages intended for them and send malicious messages in their name.

You might be wondering how this is possible when the service advertises end-to-end encryption (E2EE) as one of its flagship features. Unfortunately, E2EE has become a bit of a marketing term lately, rather than being used as the security standard/implementation that it’s supposed to be.

The researchers disclosed the vulnerabilities to Bridgefy on April 27th, 2020. Bridgefy asked them not to go public with their findings until August 20th, and the researchers complied. To Bridgefy’s credit, they began alerting their users just five days later that they shouldn’t expect confidentiality guarantees from the current version of their software. On July 8th, the developers said they began working on a switch to the Signal protocol, which is widely considered the gold standard in messaging encryption.

Bridgefy has since also removed a lot of their marketing that promised privacy or painted protests as a suitable use-case for their service.

It would not be far fetched to assume that the app was intentionally instructed by governments to use low levels of security. This is often an alternative tactic that allows authorities to intercept private communication without the need of installing a government backdoor. This is possibly why TikTok uses plain unencrypted (and easily intercepted) HTTP, for example.

That said, Bridgefy’s response to the vulnerabilities disclosed by the security researchers seems to indicate that this was an innocent oversight on their part that they’re struggling to rectify without irrevocably harming their reputation. This is certainly not a fun scandal for anyone to be on the wrong side of, especially if they were genuinely trying to protect user privacy but missed a small detail.