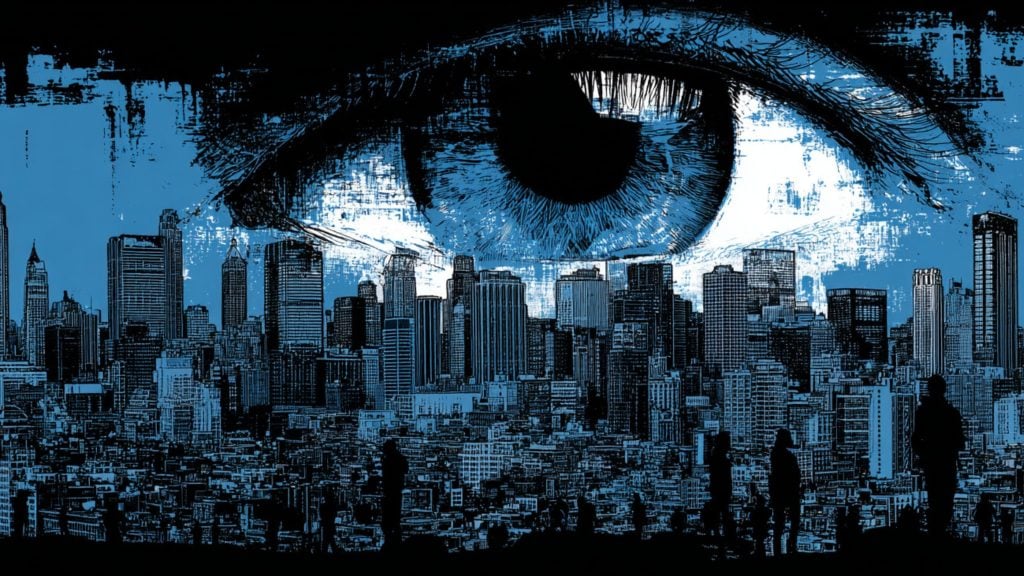

With a necessary reality check, a UK tribunal has told the government that, no, it cannot hold a secret legal battle against Apple over encryption. The Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT), the body meant to oversee the country’s surveillance powers, has dismissed efforts by the Home Office to keep the entire case hidden from public view. And in doing so, it has delivered a quietly important win for press freedom and digital rights. Although, things are far from over.

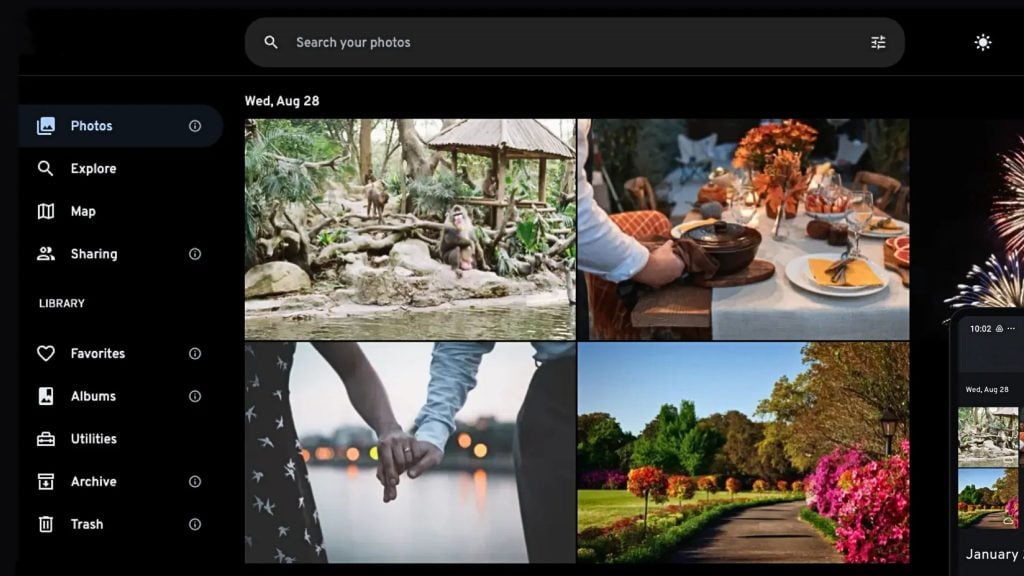

The case revolves around Apple’s Advanced Data Protection system, or ADP. It’s a security feature that gives users the option to encrypt their iCloud data in a way that even Apple itself cannot access. Not through a backdoor, not with a master key, not at all. It’s the kind of robust end-to-end encryption that governments around the world have grown increasingly nervous about.

The UK, it turns out, is no exception.

The Home Office had tried to argue that even disclosing the existence of the case could jeopardize national security. But the tribunal wasn’t persuaded. In its published ruling, it said: “It would have been a truly extraordinary step to conduct a hearing entirely in secret without any public revelation of the fact that a hearing was taking place.”

The government’s request challenged press freedom, veering into the territory of democracy-by-blindfold. The tribunal concluded that sharing “the bare details of the case” would not, in fact, bring down the roof on national security.

We obtained a copy of the judgement for you here.

So now, the legal battle moves into the public eye, where it belongs, and where the dangerous surveillance law can be challenged.

Apple’s stance has been consistent. The company says it has no technical means to access ADP-protected data, and it does not intend to build one. The rationale is simple: once you create a vulnerability in encryption, you’ve weakened the system for everyone. Law enforcement may be the intended user, but malicious actors don’t tend to respect boundaries.

Earlier this year, Apple pulled ADP from UK devices entirely, after pressure from the government. It then filed a legal challenge in March, drawing a firm line in the sand over what it’s willing to compromise.

The Home Office, for its part, insists that it isn’t trying to snoop on the public. It reiterated that any attempt to access encrypted material requires a warrant, signed off by a court. “There are longstanding and targeted investigatory powers that allow the authorities to investigate terrorists, pedophiles, and the most serious criminals and they are subject to robust safeguards including judicial authorizations and oversight to protect people’s privacy,” it said.

That’s all fine in principle. However, the government’s attempt to keep this particular legal process secret has made its definition of “robust safeguards” look worryingly vague. Transparency, it turns out, is not optional when it comes to decisions that affect the rights of millions of people.

The implications of this case don’t stop at the UK’s borders. As governments around the world weigh stronger surveillance powers in the name of public safety, Apple’s refusal, and the tribunal’s decision to force the case into the open, set a precedent.

Weakening encryption isn’t simply a matter of local law enforcement convenience. It’s a global issue that affects anyone who relies on secure communication.

The IPT has also confirmed it will hear the case brought by Privacy International, Liberty, and two individuals who are challenging the legality of the Home Secretary’s decision to use her powers to secretly compel Apple to compromise its own security systems.