The European Union (EU) is scrambling to establish tighter control of online information ahead of the elections in May for the European Parliament (EP). This effort requires cooperation from Big Tech and advertisers – who must keep “fake news” at bay, or risk EU regulation – and cooperation with partners such as NATO and G7.

The Rapid Alert System, announced late last year, whose declared goal is to allow EU member-states to “share information on ongoing foreign disinformation campaigns with one another, and coordinate responses,” has now come into effect.

Specifically, the foreign information threat the EU is looking to shield itself from is Russia, and “pro-Kremlin” disinformation. After the 2016 US presidential elections, Hillary Clinton’s campaign and supporters never accepted her defeat as the choice of American voters – but rather the result of American voters being manipulated by Russia.

Russia continues to deny these accusations, but ever since the big US election upset that saw Donald Trump become president, there have been attempts, to various degrees successful, to pin the outcome of every election and referendum in the western world that didn’t quite go the establishment’s way on Russia’s malign influence. This includes Brexit, the UK’s vote to leave the EU.

Addressing the European Data Protection and Privacy Conference, EU Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society Mariya Gabriel has now offered some insight into the way the new system is set up and meant to function.

Gabriel mentioned that US tech and social media giants and advertisers have signed up to the Code of Practice. Under the code, these companies are expected to cut off revenue streams to suspected offenders, remove their accounts, promote news from sources viewed favorably, and ensure more transparency when it comes to political advertising.

“In view of the European Parliament elections, Google and Facebook are providing training to candidates, political parties and campaigners on how to manage their online presence and on how to protect their campaigns,” Gabriel revealed during her keynote speech.

But that’s not all – since late 2018, Twitter, Facebook, and Google have been reporting to the EU on a monthly basis on the progress they made in implementing this voluntary, and self-regulatory, code. The last such “progress report” showed promise, the EU official said – but warned that “we are not yet there.” And while these companies have all implemented “a tool to monitor political ads” – not everyone is moving fast enough to remove unwanted accounts.

YouTube, for example, reported removing 600,000 in February alone – but the commissioner admitted the EU is not sure if their offense was of political or commercial nature. Facebook is yet to report its latest figures – while Twitter reported “nothing” – said Gabriel.

The European Commission has also enlisted help from “independent fact-checkers and researchers to detect and expose disinformation campaigns across social networks,” Gabriel said.

On the member-states’ side, “election cooperation networks” have been put in place to swiftly detect “potential threats,” she explained.

In the context of the initiative, the commissioner made special emphasis on data protection and privacy, linking the issue with political disinformation campaigns. Advertisers, ISPs, insurers and others collecting and misusing personal data in order to sell “shoes and cars” is one thing – but what if the same techniques are used by (bad) governments and those with vested political interest?

Gabriel differentiated between “legitimate” political processing of online users’ data, and that which brings with it “serious risks” to privacy and trust in the democratic process.

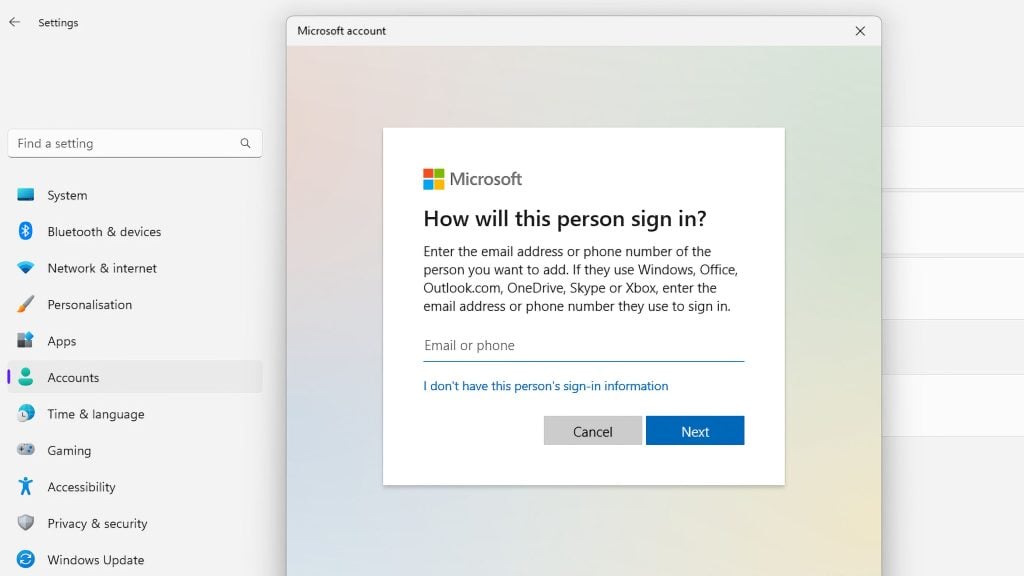

According to Gabriel, EU citizens are given protection in both scenarios by the GDPR and the e-Privacy Regulation. The GDPR stands for “General Data Protection Regulation” – a piece of legislation in place since 2018 that is seen as having good intent to give users more protection and control over their own data, but has also found its critics in being difficult to implement.

However, Gabriel praised it as having become a global standard in just under a year, and spoke strongly in favor of a “transparent, fair and lawful” manner of data collection and processing.

It’s hard to assess how effective the EU’s move to introduce these measures can and will be, but it seems unlikely to backfire as a political initiative. If the EP elections produce a status-quo, the EU could blame Russia for trying, while giving itself a pat on the back for a job well done in blocking Moscow’s interference. In the reverse scenario, the EU could blame Russia for succeeding – and push for even more regulation, more self-regulation from tech companies, and more money paid by EU member-states towards the budget of the European External Action Service (EEAS) – the implementer of the Rapid Alert System.