Just a few months after it was revealed that doctors and whistleblowers in China were detained for posting on the Weibo social network that a viral outbreak was taking place, and that social media posts raising the alarm were getting people’s accounts banned, and their messages were being censored in real-time, a Harvard University professor is suggesting that China has the right approach to regulating speech on the internet and that the US should follow the same principles.

It’s not reasonable to expect that online speech might be able to go “back to normal” after being reined in and constrained to the extreme in some extraordinary instances of surveillance and censorship accompanying the coronavirus pandemic, and justified by it, an article published by the Atlantic is incredibly suggesting.

With coronavirus, speech is being tightly controlled in online and traditional media, while Big Data is used freely by Big Tech to enforce government measures, in what would under any other circumstances be considered unacceptable mass tracking and surveillance of citizens.

But extraordinary situations require extraordinary measures, the justification goes, and, faced with an unprecedented and still unpredictable health crisis, most people are ready to go along with it.

According to the argument, even civil and digital rights activists begrudgingly accept the necessity to sacrifice freedom of speech and personal privacy at this moment, saying at the same time that they also expect these measures to be gone once the health threat is gone. But they probably know better.

And while things will never be the same after the drama is over, as history teaches us, they needn’t get worse, either.

However, that is not something two law professors, Jack Goldsmith and Andrew Keane Woods, anticipate as they make this extraordinary claim: that China got it right with a policy that resulted in its iron-fist internet censorship policy, and that China is in that regard now becoming a role model for the United States.

“In the great debate of the past two decades about freedom versus control of the network, China was largely right and the United States was largely wrong,” Jack Goldsmith of Harvard Law School and Andrew Keane Woods of the University of Arizona shockingly wrote.

Then for the jaw-dropper: “Significant monitoring and speech control are inevitable components of a mature and flourishing internet, and governments must play a large role in these practices to ensure that the internet is compatible with a society’s norms and values,” they add.

The argument, which seems to be primarily focused on making a case for the necessity of (much) more regulation of the online space in the US, describes the internet as a vehicle to disseminate American values around the world, all the way to helping foster revolutions and topple authoritarian governments, using the sheer force of its promise of freedom of speech. If only.

However, China took the tech, but left out the political and ideological message that the authors purport was behind the internet. Where America went “unregulated,” China and its ruling Communist Party (CCP) decided to regulate, and then some – building an imposing system of stringent control and censorship.

The law professors intersperse large chunks of summaries of some of the best-known and notorious examples of increasing censorship and mass surveillance online in the western world, with the argument that digital speech produces serious harm. (Mostly this has to do with Russia supposedly using the internet to whip up what is referred to as “the 2016 election debacle.”)

And in order to make sure digital speech is no longer so harmful, the notion of the impossibility of returning to an “unregulated normal” is being subtly normalized throughout the argument.

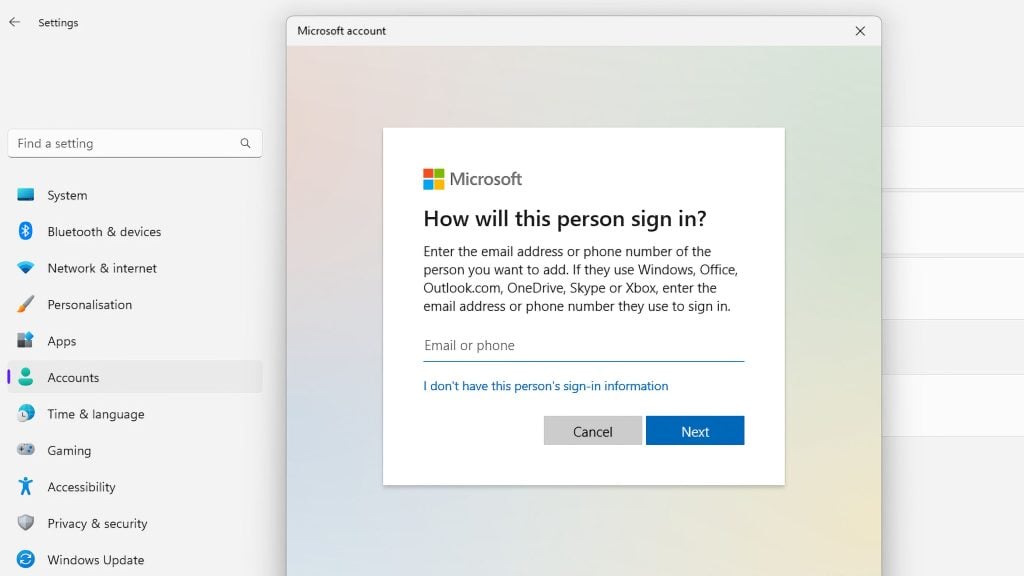

The authors also assert that the difference between China’s online surveillance and speech – and population control – and that currently at play in the US is that the former is government-driven, while the latter at the moment relies mostly on the power private tech corporations have over data.

Both models are presented as aggressive and extensive in different ways and with different goals in mind.

Digital speech meanwhile is predicted to continue to cause more and more “harms” – which makes speech control inevitable on online networks, say Goldsmith and Keane Woods.

“And invariably, government involvement will grow,” they say, adding, “It is also unclear whether, for example, the companies can adequately contain foreign misinformation and prevent digital tampering with voting mechanisms without more government surveillance.”

There are “social costs” involved with an open internet, they continue, and Americans’ distaste for government involvement in private companies’ affairs will be put to the test with these perils of online speech predicted to be growing in the future.

Referring to it as an experiment that lies ahead on the other side of the coronavirus pandemic, the argument speaks of the US Constitution and its current interpretations “adjusting” to the country’s future digital realm.

All this is further reinforced by making a note that even European countries that have made privacy an important part of their national policy now “seem” to agree with more surveillance.

At the same time, privacy activists who want more accountability from the likes of Google and Apple at this time are rebuffed by legal commentators who say the giants are actually “too-protective”.

Too much privacy produces “a design that raises far too many barriers to effectively tracking infections,” Stewart Baker is quoted as saying.

All arrows point towards “the general trend toward more speech control” not abating any time soon and the tone of the article suggests the authors can’t wait for it.