It’s not exactly news at this point: law enforcement agencies are increasingly seeking Big Tech’s cooperation in giving them access to massive data sets taken from users of social networks and other online platforms and services.

And although some reports now address this topic in the context of the way these powers were used during the Trump era Department of Justice (DoJ), the practice neither started, nor ended with the previous US administration.

Instead, over the past six years, there has been a steady and entirely predictable rise in requests for detailed personal data that Big Tech collects from users and their devices. The more data – the more requests.

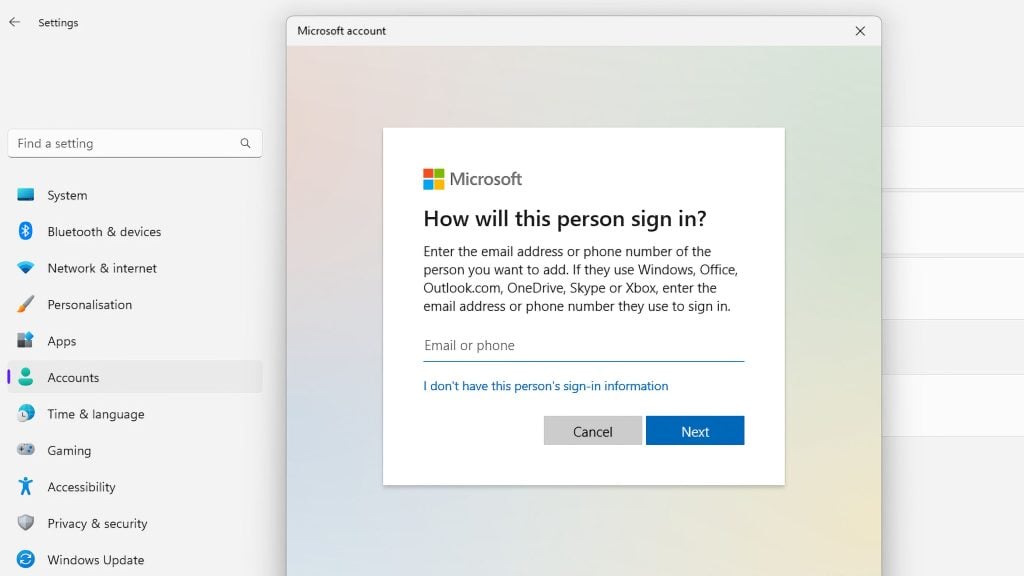

The latest available statistics from the first half of last year show that Apple, Google, Facebook and Microsoft received three times more requests for information about users’ calls and emails, and content like photos and texts, compared to 2015. But tech giants collect – and hand over – much more than that, shopping and driving route history being some of the data harvested thanks to map and payment apps.

In the first half of 2020 alone US law enforcement asked for this data a total of 112,000 times – and Big Tech complied either fully or partially in 85% of cases. Facebook and Instagram in particular, having the largest combined user base, also topped this list.

And while the behemoths say that most of that data is “non-content” – such as metadata – user’s privacy is not much better off for it, considering that identifiable information can clearly be extracted from multiple correlated metadata points.

In a recent report, AP cites the case of Newport, a small town with a large tourist industry, whose police department is now increasingly relying on obtaining data from tech companies when investigating crimes.

“The amount of information you can get from people’s conversations online – it’s insane,” Newport supervising detective Robert Salter shared with the agency.

Digital privacy groups like the EFF call this “the golden age of government surveillance” as law enforcement not only has more access to data, but is also more prone to using gag orders, leaving its targets unawares.

The EFF suggests tech companies use strong encryption as one remedy to the police “short-circuiting constitutional protections against unreasonable searches.”