YouTube is suspected of catering to the music industry at the expense of the interests of its users to the point of potentially breaking the law.

Specifically, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) – a US law passed in 1998, criminalizing copyright infringement. And although the law itself is controversial and fraught with problems, another level is reached if a company such as YouTube makes a violation in the process of implementing it.

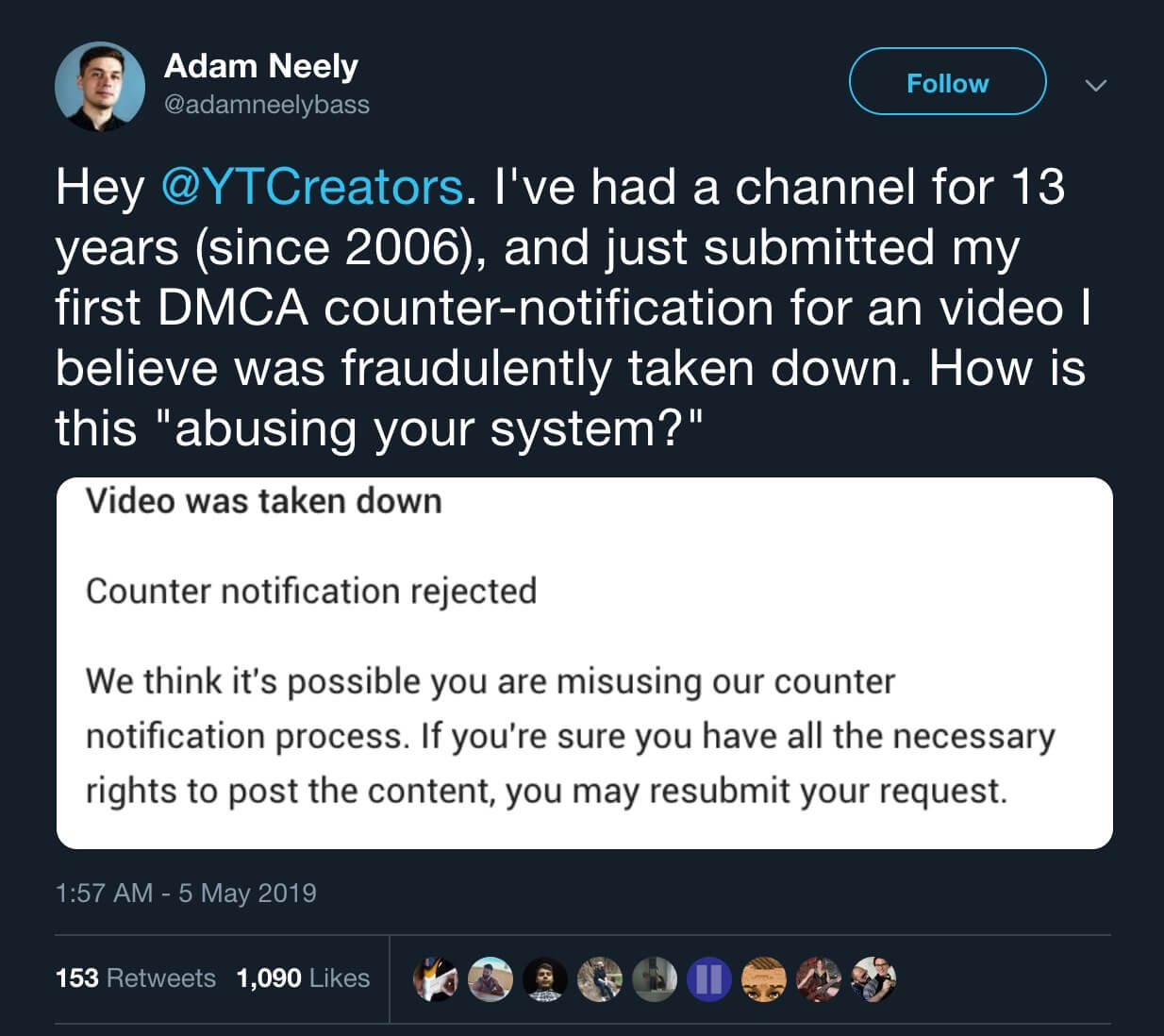

The suspicion arose after musician and YouTuber Adam Neely received a DMCA takedown notice over one of his videos, a “Single Ladies” analysis, and attempted to fight back with a counter-notice claiming fair use – in line with DMCA rules. But YouTube rejected it, saying it “appeared” he had no right to post the said content.

Fair use is designed to allow limited use of copyright content without the need to obtain permission from rights holders and is aimed at ensuring that public interest is balanced out with that of copyright owners.

Copyright attorney Leonard French analyzes the case on his legal education channel Lawful Masses, to say that he believes this represents a violation of the DMCA. In a video entitled, “YouTube’s DMCA Double Standard” he notes that Neely asked YouTube in a post on Twitter what documented evaluation had been conducted to prove that the video in question was not covered by the fair use rule, with commenters expressing surprise, noting that it should be impossible to reject a DMCA counter-notice.

But Neely clarified that he was informed it was officially YouTube’s policy to reject (DMCA) counter notifications “in some cases.”

However, under the law, the rights holder must either sue within two weeks of receiving a counter-notice, or YouTube must restore the video. But in this case, Neely was told that his counter-notice was not even forwarded to the original claimant.

And while YouTube itself is protected under the DMCA as a safe harbor – meaning that Neely could not sue them for removing his content, that’s only true as long as the company has not renounced its safe harbor status – by entering into agreements with copyright owners, in this case, music companies. But how can YouTube refer to DMCA in its original takedown notices, that to then automatically reject counter-notices contrary to the DMCA rules?

These agreements, that the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a digital rights group, refers to as “anti-user,” mean that the usual ways to dispute copyright claims are no longer available to those affected by takedown requests.

“These agreements are opaque, and scope of what’s allowed under them is unknown. They may be short-term, or long-term. Fair use is dealt a serious blow under these agreements,” says EFF.

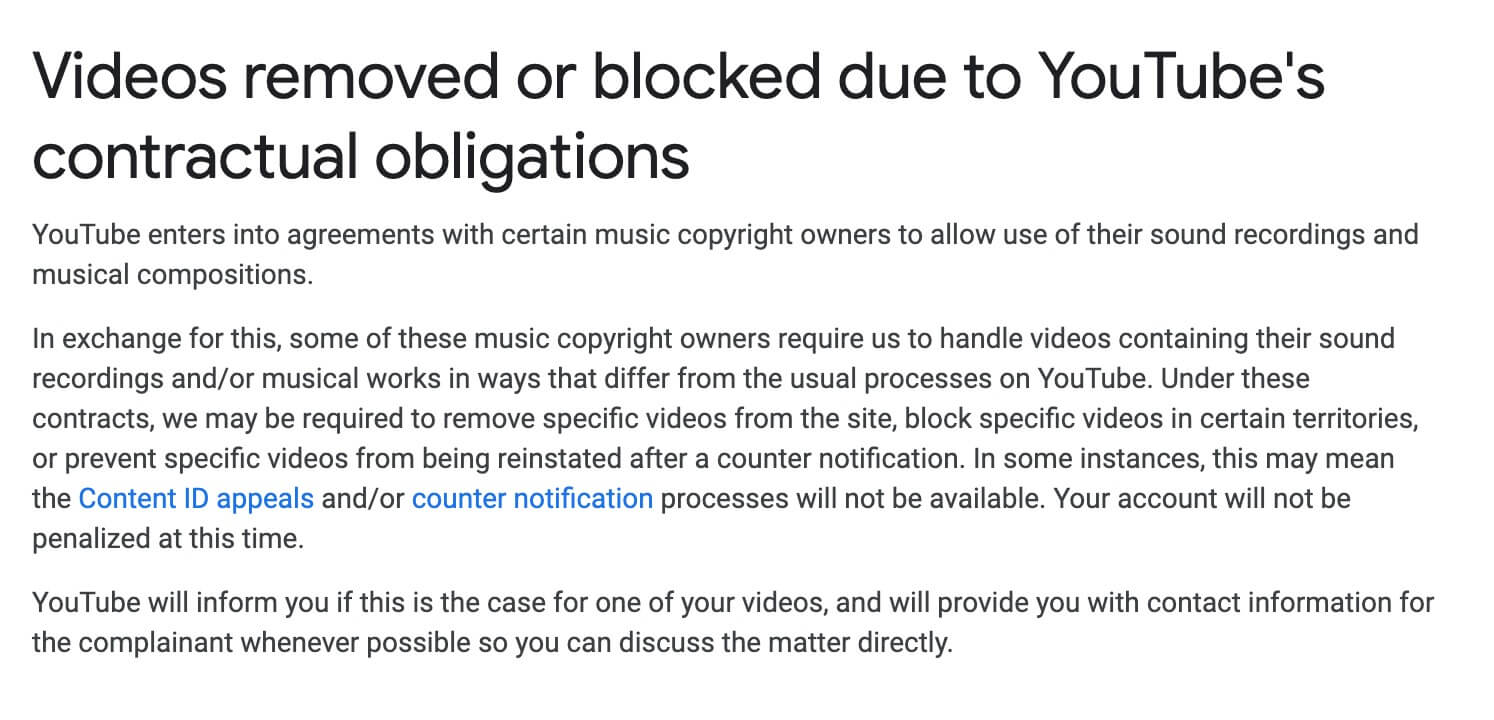

And this is not exactly something that YouTube is trying to keep a secret, either: a reply posted on the support forums of YouTube owner Google dedicated to videos removed or blocked due to the company’s “contractual obligations” says that it “enters into agreements with certain music copyright owners to allow use of their sound recordings and musical compositions.”

“In exchange for this, some of these music copyright owners require us to handle videos containing their sound recordings and/or musical works in ways that differ from the usual processes on YouTube,” Google said, adding that while the contracts require that videos are removed or blocked in some parts of the world, “or prevented from being reinstated after a counter notification” – potentially resulting in Content ID appeals and/or counter notices becoming an unavailable option.

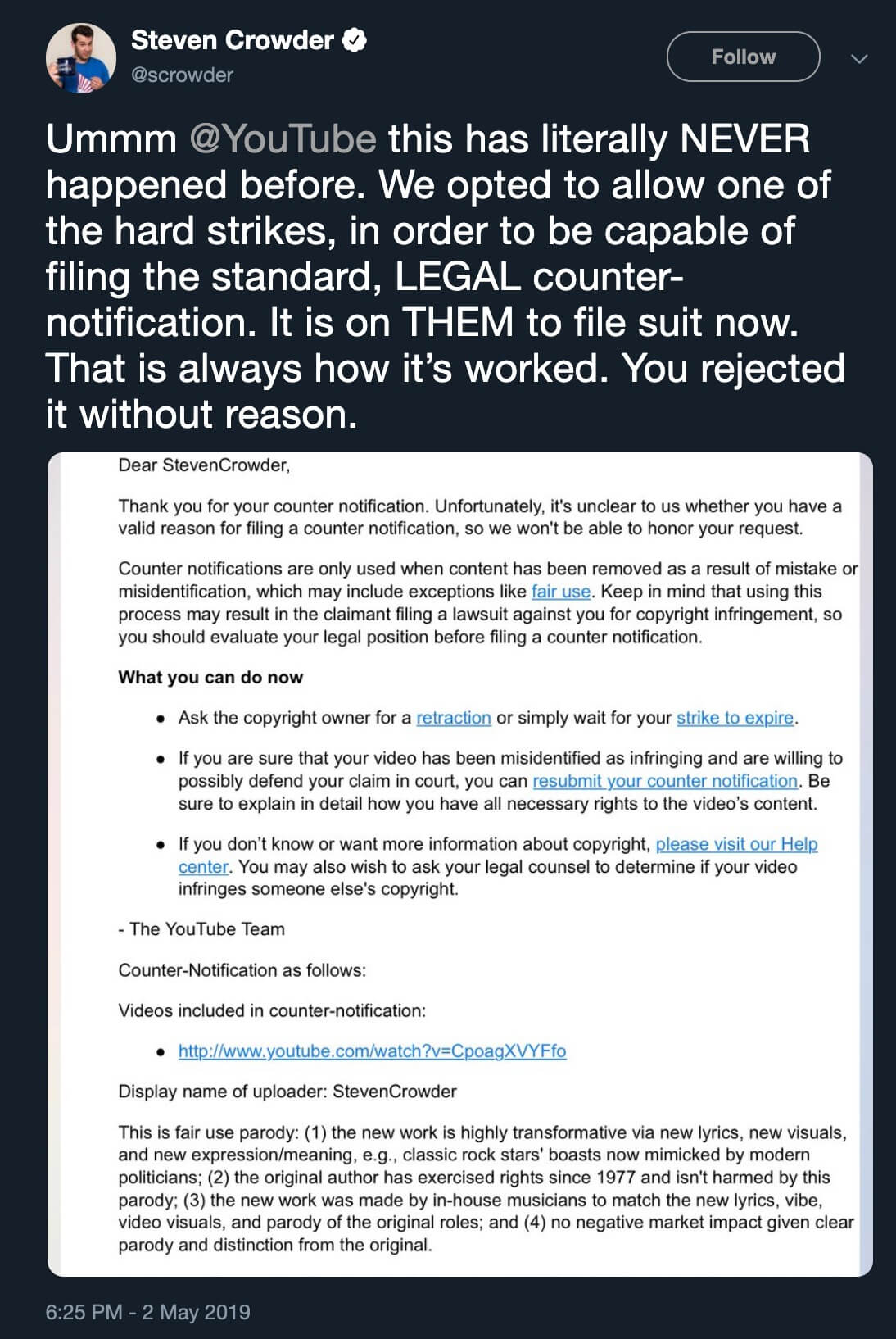

Meanwhile, another YouTube user, Canadian-American conservative commentator and actor Steven Crowder has been hit with a similar takedown conundrum.

Posting on Twitter, he said that this issue never occurred before, and added: “We opted to allow one of the hard strikes, in order to be capable of filing the standard, LEGAL counter-notification. It is on THEM to file suit now. That is always how it’s worked. You rejected it without reason.”

All this suggests that YouTube may be on one hand using a DMCA provision to file takedown notices – and also afford itself the status of a safe harbor – to then act contrary to the same law and refuse counter notices without even considering them. This would be illegal, as, under the DMCA, copyright holders must conduct legal analysis before the content is taken down – otherwise they would be disregarding the fair use doctrine enshrined in the legislation and become liable for any takedown.

French speculates that this means YouTube and copyright holders likely have deals in place guaranteeing that YouTube would be compensated for any financial loss that may occur from lawsuits filed over this practice – i.e., not being in its safe harbor.

He further recommends that those YouTube users affected by such illegitimate notices get in touch with a copyright attorney and sue for either copyright infringement or contract violation, and concludes that while those hit with such decisions made by YouTube can do something to rectify the situation – this would have to be done in court.