Public Wi-Fi is where your use of the internet may be at its most vulnerable, technically speaking – it’s where the security of your connection with the rest of the online world becomes so unpredictable that it can be assumed to be broken down – unless tools like VPNs are put in place.

It makes sense then, that you might want to keep the way your devices – and associated bank and email accounts and passwords, along with a trove of other private and valuable data – is surfaced on the internet safely.

Therefore, it’s hard to say how many people would trust Facebook of all things to manage this critical task on their behalf – yet that is something Facebook, notorious for its disregard of security and for routinely misusing personal data, really wants to do.

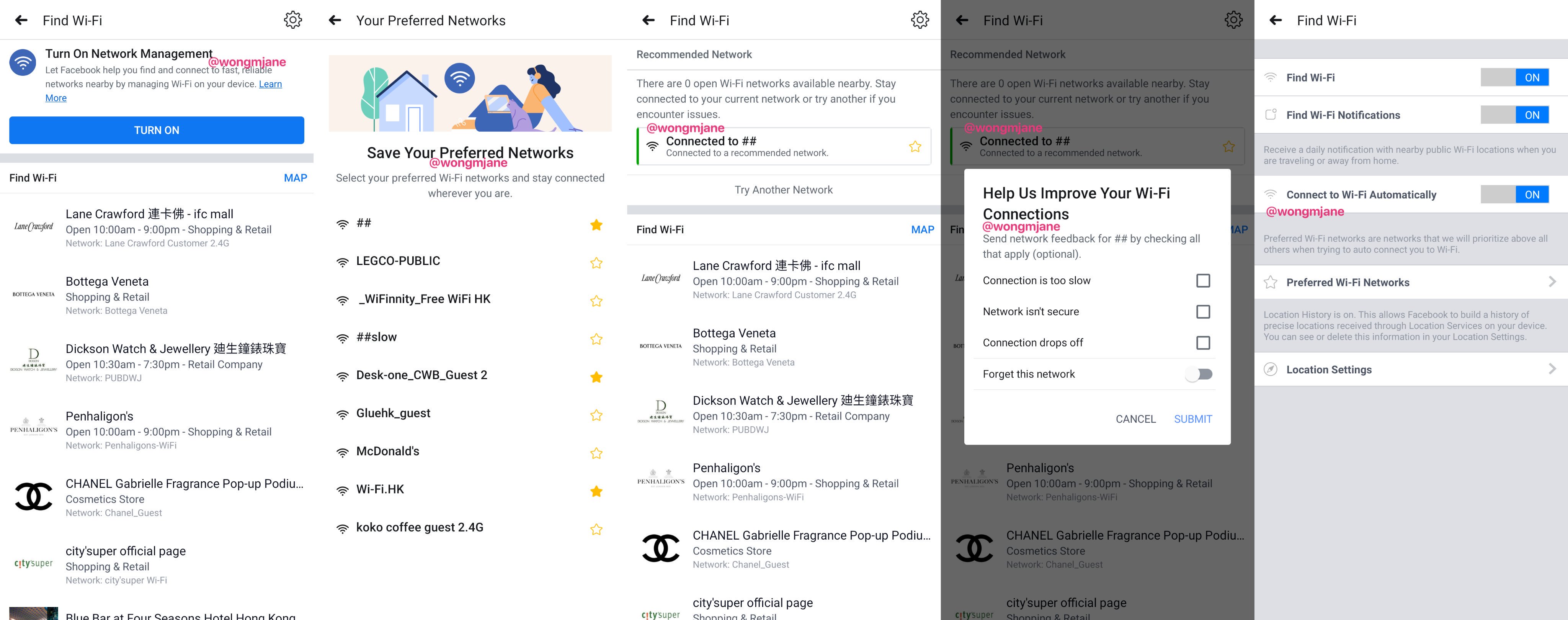

App researcher Jane Manchun Wong writes on her blog that a Facebook feature for the Android app, yet to be released, aims at broadening the original “Find Wi-Fi” feature first introduced two years ago.

Click here to display content from X.

Learn more in X’s privacy policy.

Find Wi-Fi was explained by Facebook at the time as something designed to help users who might be traveling, or for another reason unable to use their mobile data.

Wong now writes that if turned on, the way the feature works is by letting Facebook know about a user’s location “periodically.” This is done in order to correlate networks data into one big hive.

Wong also revealed that when after she “came across an endpoint in Facebook’s server which belonged to the same project” – and one that “returned approximately 13,000 networks in Manhattan” – and after letting others know about it in a tweet – Facebook blocked her access to the endpoint.

Click here to display content from X.

Learn more in X’s privacy policy.

The endpoint, that is now showing as empty, originally revealed “the name of each Wi-Fi network, the signal strength and the approximate coordinate of each network,” the blog post said.

The author further speculates that Facebook may have gotten access to the massive list of these by and large residential networks by harvesting data from users who allowed the app to access their location.

Wong adds that on Android, apps are allowed to collect this type of data from time to time – in order to facilitate sharing it with advertisers.

“By crowd-sourcing Wi-Fi networks and associate them with geolocation data, companies can determine relations between users, for example, whether they are roommates, neighbors, colleagues, where they work, etc. This allows targeting ads more precisely,” Wong writes.