Life has been rapidly changing in Hong Kong over these last few weeks as a consequence of the enactment of China’s new security law.

Critics say that although its stated goal is to shore up the country’s national security by preventing secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces, the real reason Beijing has reached for this legal solution is to tighten the screws on Hong Kong, that had been rocked by many months of pro-democracy protests over the past year and a half.

The way in which the authorities are already implementing the law suggests that it does actually aim to step up control of speech and political and other opposition activity in the territory.

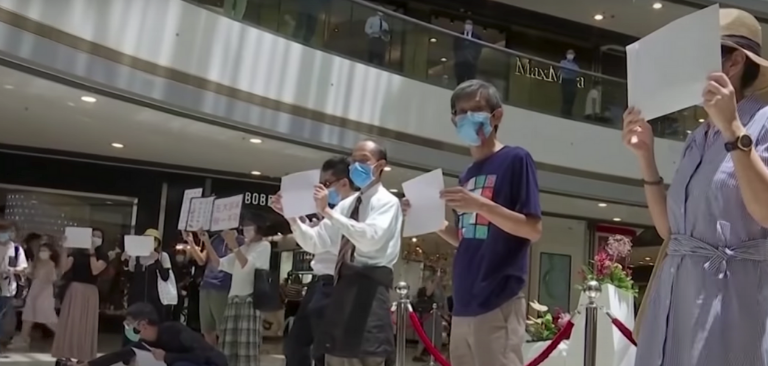

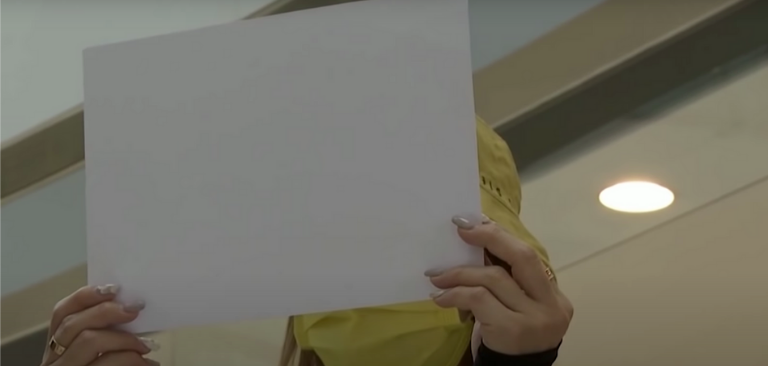

Among the most notable of incidents is the recent arrest of eight people in a shopping mall for the “crime” of holding blank sheets of paper. It was clearly a form of protest, and the authorities recognized it as such, sending in riot police to make arrests and remove others from the site, in this way sending the message that no virtually no form of protest is now allowed.

The display of a blank paper, however, is a powerful message in its own right, as those who came up with it said they no longer knew what is still legal to express in this territory, that has been known for pro-democracy groups and vibrant business and artistic communities that are now being muzzled.

But these arrests is far from the only such incident, as hundreds of others have been detained in the two weeks that the law has been in force, including for displaying protest slogans or quotes from the Bible. At the same time, many books written by pro-democracy authors are no longer available in public libraries.

When the police stormed the Public Opinion Research Institute this week, they seized the pollster’s computers acting on a warrant citing “dishonest use” of the machines. This organization has been involved in organizing election primaries for pro-democratic legislators, and in publishing surveys exposing unfavorable opinions of the government and police.

In Hong Kong there is an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty, and provides more evidence that some Hong Kong residents are taking Beijing’s determination to establish control very seriously – by sliding into self-censorship.

Although school libraries were told they were free to make their own call on what books to allow, many are removing those dealing with, for a variety of reasons, highly sensitive to Beijing and often censored topics like the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Cultural Revolution, Taiwan, and Hong Kong’s own colonial past.

One coffee shop owner removed posters and other artwork supportive of the protests, reacting to what she describes as indirect pressure – owners of establishments such as hers having the validity of their licenses questioned, with both shops and staff who supported protesters coming under physical attack in some cases.

The protests started over a year ago when the Hong Kong residents rose up against a proposed law that would have allowed extradition to mainland China. But even though this draft was later withdrawn, the pro-democracy demonstrations continued – and now, with the new national security law, the same extradition provision has once again appeared, and has been enacted.

This time discontent is expressed in more subtle ways, with those who removed large displays of images and messages from the protests now putting up walls of blank Post-it notes.

New cartoons and graffiti appearing in Hong Kong are true to the same theme, namely, of “wordless resistance” – as Beijing is accused by observers of using the opportunity to enact the new law and start imposing the new rules as the world is gripped by other concerns, like the coronavirus pandemic.

And while many are trying to protect themselves and their businesses, others say they intend to remain defiant and not bow down to pressure. One of the women arrested in the shopping mall was seen raising a blank paper as soon as she was charged and released from the police station. Talk about dedication.