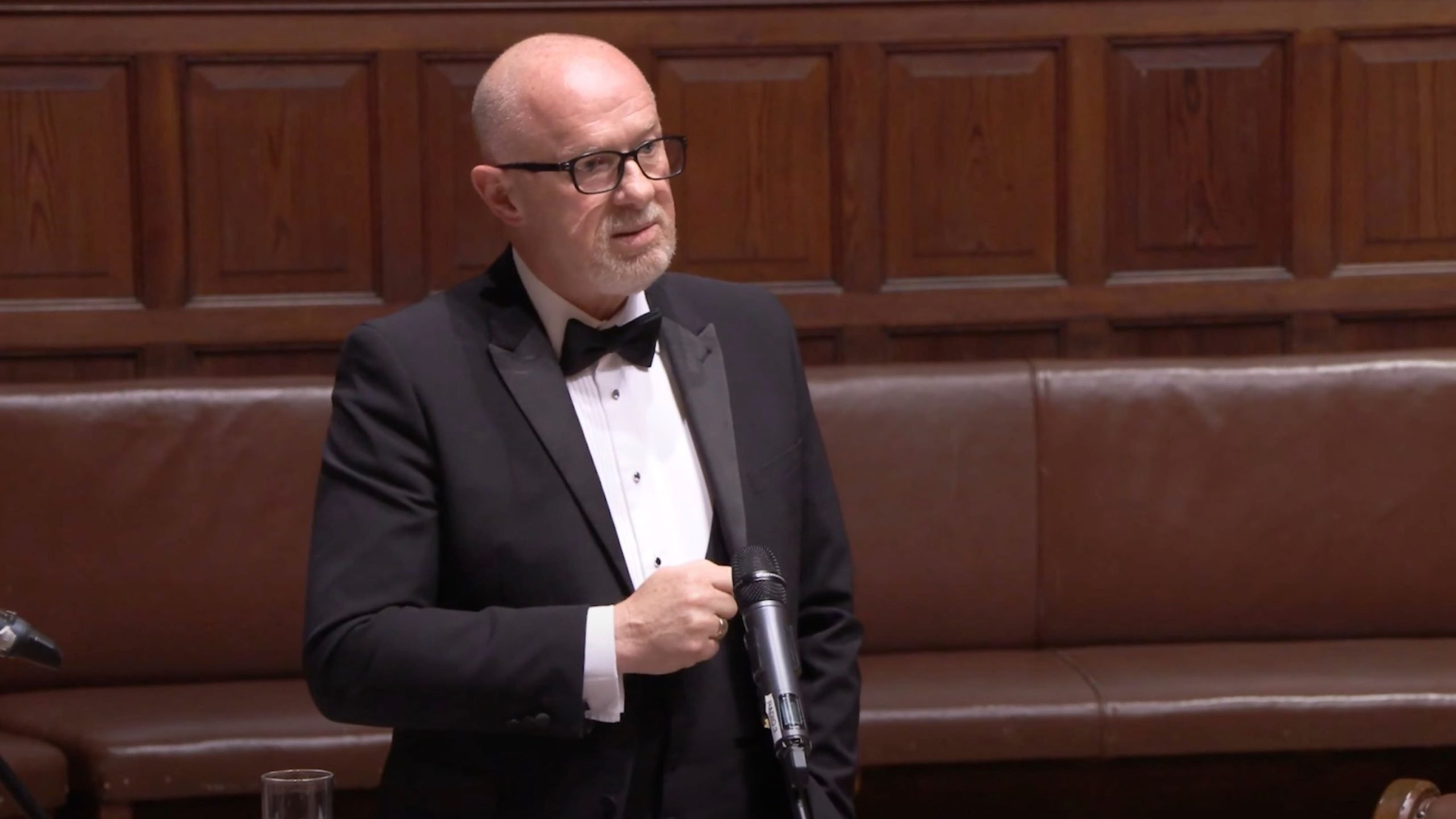

UK’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary Andy Cooke, and the Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS), continue to focus on online speech (social media) in an attempt to explain last year’s Southport riots, and how similar scenarios should be prevented going forward.

And while critics continue to heap criticism on the Online Safety Act as going too far and effectively serving as a sweeping online censorship and age verification law – the problem Cooke sees is that neither the law nor its enforcer, the regulator Ofcom, are going far enough.

Cooke is not satisfied with how quickly what was deemed by the authorities as misinformation got removed from social networks last summer and believes that if Ofcom were to be given additional powers, that “problem” might be solved.

More: UK PM Keir Starmer Uses Riots To Call For Mass Surveillance and Social Media Censorship

His argument is that the Online Safety Act is limiting Ofcom’s “capacity and capability” to delete online content so quickly as to rule out the ability of this information “spreading virally.”

When trying to contain speech around events like the 2024 rioting and protests, as things stand now, the law has “little or no bearing” – according to Cooke.

However, judging by Ofcom’s reaction, he may not properly understand the regulator’s role in enforcing the Act. The speed of this kind of censorship is not the issue, since Ofcom is not supposed to do that in the first place.

The regulator told the BBC that it “cannot assess individual pieces of content or take down specific posts” but is supposed to force platforms to implement systems and processes that will “protect people from illegal material, and ensure children do not encounter other harmful content.”

This can be interpreted as meaning that the law, and Ofcom, serve the purpose of “systemic” rather than “per-post” censorship.

Meanwhile, a recent HMICFRS report found that causes of the Southport riots were “complex” – and were not premeditated, or coordinated.

More: Keir Starmer’s Censorship Playbook

Criminal factions and extremists were not involved, either. And so, “inspectors said that it was mostly disaffected individuals, influencers or groups that incited people to act violently and take part in disorder.”

The report decided to put the hard but essential issue of the complexity of the causes aside – and emphasize “the overwhelming speed and volume of online content” that “further fueled (disorder’s) spread.”

Reacting to all this, the Big Brother Watch civil rights campaigner recalled its investigations into previous instances of the authorities policing speech during crises, such as during Covid.

“The Government or media regulators should not be given a blank check to decide what we can read, see, or hear,” the group said in a post on X. “At times of unrest, we need to protect our democratic rights with more vigor, not less.”