At a recent UK parliamentary hearing on social media and algorithms, lawmakers ramped up calls for increased censorship online, despite revealing that they themselves remain unclear on what the existing law, the Online Safety Act, actually covers.

The session, led by the Science, Innovation, and Technology Committee, displayed a growing appetite among MPs to suppress lawful speech based on subjective notions of harm while failing to reconcile fundamental disagreements about the scope of regulatory authority.

Rather than defending open discourse, members of Parliament repeatedly urged regulators to expand their crackdown on speech that has not been deemed illegal. The recurring justification was the nebulous threat of “misinformation,” a term invoked throughout the hearing with little consistency and no legal definition within the current framework.

Labour MP Emily Darlington was among the most vocal proponents of more aggressive action. Citing the Netflix show Adolescence, she suggested that fictional portrayals of misogynistic radicalization warranted real-world censorship.

She pushed Ofcom to treat such content as either illegal or misinformative, regardless of whether the law permits such classifications. When Ofcom’s Director of Online Safety Strategy Delivery, Mark Bunting, explained that the Act does not allow sweeping regulation of misinformation, Darlington pushed back, demanding specific censorship powers that go well beyond the legislation’s intent.

Even more revealing was the contradiction between government officials themselves. While Bunting maintained that Ofcom’s ability to act on misinformation is extremely limited, Baroness Jones of Whitchurch insisted otherwise, claiming it falls under existing regulatory codes.

The discrepancy not only raised concerns about transparency and legal certainty but also highlighted the dangers of granting censorship powers to agencies that can’t even agree on the rules they’re enforcing.

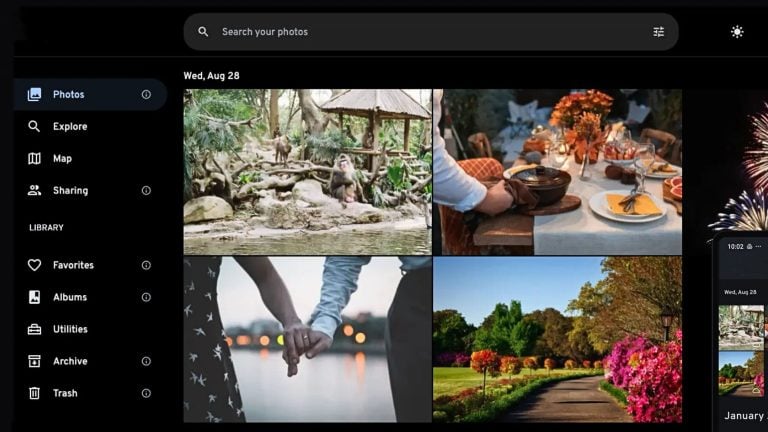

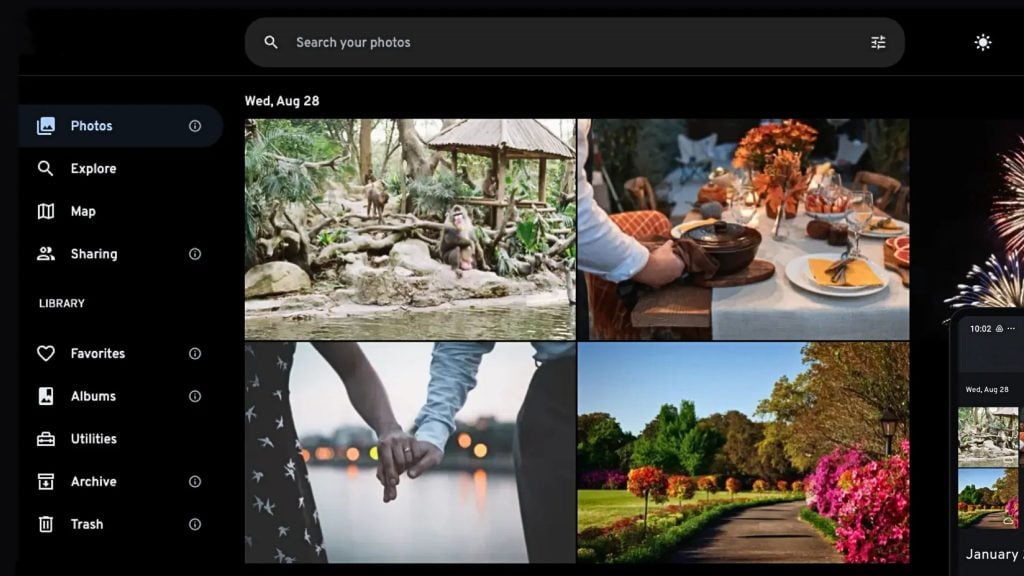

John Edwards, the UK Information Commissioner, shifted the discussion toward algorithmic data use, arguing that manipulation of user data, especially that of children, could constitute harm. While Edwards did not advocate direct censorship, his remarks reinforced the broader push for increased state oversight of online systems, further blurring the line between content moderation and outright control over public discourse.

Committee Chair Chi Onwurah repeatedly voiced dissatisfaction that misinformation is not explicitly addressed by the Online Safety Act, implying that its exclusion rendered the law ineffective.

However, as Bunting explained, the Act does introduce a narrowly defined “false communications” offense, which only applies when falsehoods are sent with the intent to cause significant harm—a standard that is both difficult to prove and intentionally limited to avoid criminalizing protected expression. Onwurah appeared unimpressed by these legal safeguards.

Labour MP Adam Thompson pressed Ofcom to go further, asking why platforms weren’t being forced to de-amplify what he described as “harmful content.” Once again, Bunting noted that Ofcom’s mandate does not include blanket powers to suppress misinformation, and any such expansion would require new legislation. This admission did little to curb the committee’s broader push for more centralized control over online content.

The hearing also ventured into the economics of censorship, with several MPs targeting digital advertising as a driver of “misinformation.” Despite Ofcom’s limited remit in this area, lawmakers pushed for the government to regulate the entire online advertising supply chain. Baroness Jones acknowledged the issue but offered only vague references to ongoing discussions, without proposing any concrete mechanisms or timelines.

Steve Race, another Labour MP, argued that the Southport riots might have been prevented with a fully implemented Online Safety Act, despite no clear evidence that the law would have stopped the spread of controversial, but not illegal, claims. Baroness Jones responded by asserting that the Act could have empowered Ofcom to demand takedowns of illegal content. Yet when pressed on whether the specific false claims about the attacker’s identity would qualify as illegal, she sidestepped the question.

Ofcom’s testimony ultimately confirmed what civil libertarians have long warned: the Act does not require platforms to act against legal content, no matter how upsetting or widely circulated it may be. This hasn’t stopped officials from trying to stretch its interpretation or imply that platforms should go further on their own terms, an approach that invites arbitrary enforcement and regulatory mission creep.

Talitha Rowland of the Department for Science, Innovation, and Technology attempted to reconcile the contradictions by pointing to tech companies’ internal policies, suggesting that platform terms of service might function as a substitute for statutory regulation. But voluntary compliance, directed by unelected regulators under mounting political pressure, is a far cry from a transparent legal framework.

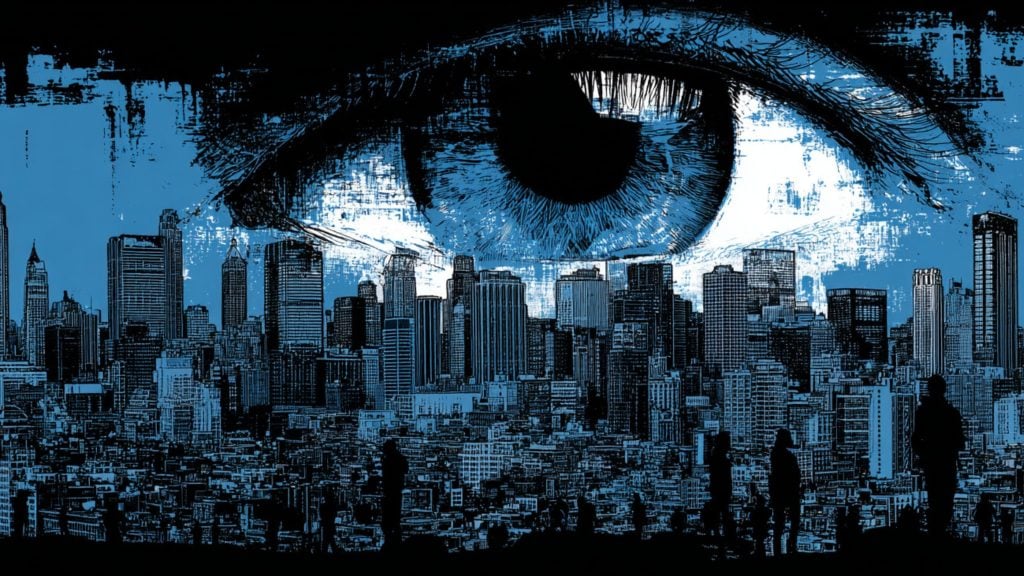

The entire hearing revealed a troubling dynamic: politicians eager to police online speech, regulators unsure of their actual powers, and a legal environment where vague definitions of “harm” are increasingly used to justify censorship by default.

The confusion among lawmakers and regulators alike should raise red flags for anyone concerned with due process, democratic accountability, or the right to express dissenting views in an open society.