Somewhere between Black Mirror and a parliamentary white paper, Netflix birthed Adolescence — a four-part drama so hyped it makes The Crown look like daytime TV. Critics have already crowned it “the most brilliant TV drama in years” and even “complete perfection.” Which, in TV review terms, is about one notch above canonizing it and placing a shrine on Rotten Tomatoes, where it currently sits at a smug 99%.

But before you’re guilted into watching it by your friends, your family, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer, or a “digital safety ambassador,” you might want to know what you’re in for. Because beneath the mournful soundtrack and teary-eyed monologues lies a playbook, not just a plot.

A Knife, an Emoji, and a National Panic

Adolescence follows Jamie, a supposedly normal 13-year-old who one day stabs a female classmate to death — triggered, we’re told, by an emoji implying he’s undateable.

You’d think such a sensationalist plot might provoke some tough questions about plausibility. Instead, it inspired a collective swoon and a full-blown moral crusade. Apparently, the line between a TV drama and a legislative blueprint has all but disappeared.

Writer Jack Thorne and actor Stephen Graham — who stars as Jamie’s heartbroken dad Eddie — aren’t merely promoting a show. They’re touring like policy consultants, meeting MPs, and calling for “serious change.” Or as Thorne put it, “We do believe perhaps the answer to this is in parliament and legislating – and taking kids away from their phones in school and taking kids away from social media altogether.”

Which is great, if your dream of the future involves biometric logins for Minecraft.

When Drama Becomes Policy Proposal

The show is more than a series about a disaffected teen gone rogue. It’s a calculated nudge that comes at the same time as a much bigger campaign — a 21st-century panic attack over children, tech, and the internet, that’s being used to promote censorship and surveillance. If the producers had their way, Adolescence would be shown in schools and parliament.

Even Prime Minister Keir Starmer got in on the act, grandstanding at Prime Minister’s Questions about “violence carried out by young men, influenced by what they see online.” Nothing gets a politician’s pulse racing like the scent of bipartisan panic and a chance to legislate online speech and increase surveillance.

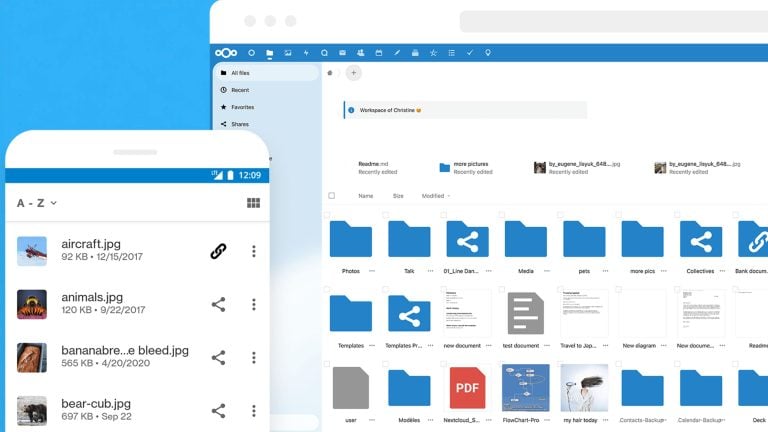

Thorne, sensing his moment, threw Australia into the mix. The country has passed laws threatening platforms like TikTok and Instagram with $32 million fines if they allow under-16s to exist online.

Which, of course, means the introduction of digital ID.

Thorne, obviously never one to aim low, said: “I would extend it further… it is about gaming too, and it’s about getting inside all these different systems.”

Jamie, the show’s mopey, hoodie-clad antihero, serves as the vessel for every contemporary anxiety about teenage boys. He’s alienated. He’s angry. He watches YouTube videos laced with “toxic masculinity.”

Thorne describes him as someone who feels “isolated” and finds “the answer to his pain” in online content. You’d almost forget this is fiction. The creators aren’t interested in ambiguity. They’re here to evangelize — about influencers, incel culture, and the urgent need for supervision of the internet, preferably enforced by law.

It’s convenient messaging. It just so happens to align perfectly with a growing movement toward digital ID which would tie everything you say to your real-world ID, content filtering, and the warm embrace of algorithmic babysitting.

All in the name of “safety“, of course.

Stephen Graham and Jack Thorne are now scheduled to appear before Parliament, invited by Labour MP Josh McAlister. Presumably, they’ll deliver heartfelt monologues about trauma, policy, and the perils of Instagram. The script practically writes itself.

But let’s not pretend Adolescence is just entertainment. It’s media-as-message, a tearjerker-as-toolkit for ushering in broad digital reforms that will affect everyone, not just hormonal teenagers with too much screen time.

Digital rights supporters should be sounding the alarm. Under the guise of online safety, what’s really coming is a regime of ID requirements, content policing, and mass data collection. But in a media landscape where feelings trump facts and fictional stabbings become case studies for policy, those warnings barely register.