In 2014, Anita Sarkeesian became one of the figures at the center of the massive Gamergate controversy after challenging the gaming industry through her lens as a “feminist media critic.”

A polarizing figure, her activism – or “media criticism,” if you like – has earned her a star status among some, and strong disapproval from others.

Duke University’s Keenan Institute for Ethics is publishing a series of interviews now, including one with Sarkeesian.

Asked about “the primary ethical dilemma” in modern media, Sarkeesian first brings up YouTube’s algorithms.

At its core, YouTube is a money-making machine for Google that sells ads and readily sways its policies according to pressure, to protect that business.

But Sarkeesian also sees it as “a modern-day soapbox” that’s “incredibly important for discourse.”

There are various reasons why observers criticize YouTube’s use of algorithms to surface, promote or downgrade content, but Sarkeesian specifically takes on YouTube recommendations and the algorithm behind it.

This talking point has become a favorite on the progressive spectrum of the US political and media scene – ostensibly because it is not controlled tightly in a way they would like, and instead allows content to become visible that they believe should be hidden.

YouTube’s main concern is to securing more engagement from users – but the thinking seems to be that if pressured hard enough, the giant might “tweak” the algorithm even more to the detriment of its own business.

Sarkeesian gives an example of what she thinks is wrong: “You watch one of my videos and it says ‘You like feminism? Here’s a whole bunch of anti-feminist videos. You’re going to love this’. You can very easily go down a rabbit hole.”

The argument seems to be that users should be kept strictly in their echo-chambers, and that being exposed to a different point of view is “a rabbit hole.”

Yet, Sarkeesian debunks herself and says that when you land on one video, YouTube presents recommended videos offering a different perspective.

A variety of perspectives is far from a rabbit hole.

It’s unclear if the rabbit hole argument works the other way around – is it problematic to watch an anti-feminist video and be recommended a bunch of feminist ones?

The theme of keeping information and the message “on brand” all the time surfaces again when Sarkeesian names what she sees as another “ethical” problem in media: hosts whose guests are not carbon-copies of themselves.

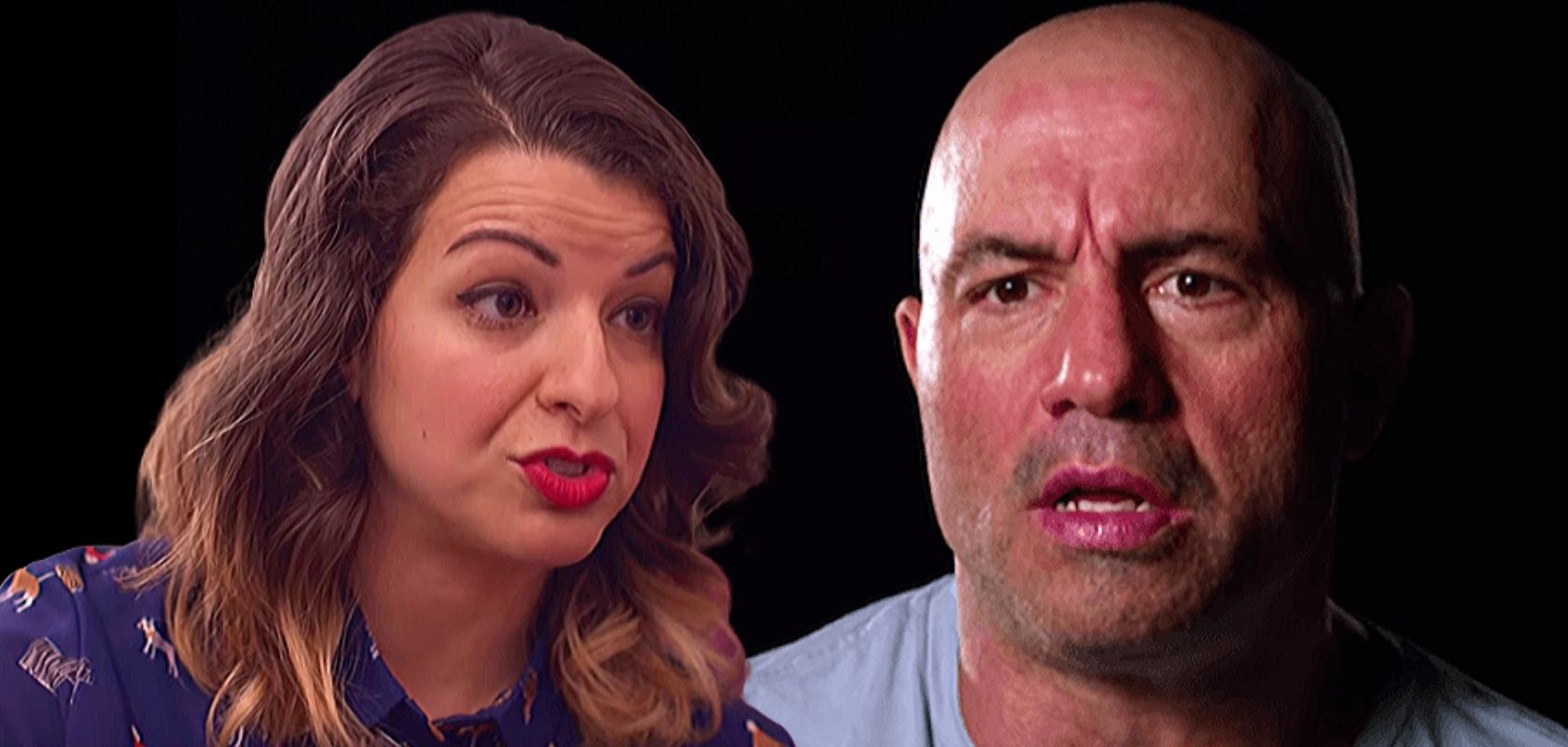

Take Joe Rogan.

“You might see let’s say a video of Joe Rogan and you’re like, ‘Oh cool, this guy is interesting. He interviews interesting people.’ And then you start to watch all of his programming and you start to see who he brings on.

“While you think what he’s saying is totally reasonable, but his guests might say some things that are a little extreme, a little wacky, or a little conspiracy theorist and might begin to think, ‘But if this guy who I’ve been watching for a while thinks he’s cool, then maybe he is.’ And then you go down that rabbit hole.”

Logic dictates that a host and their guests agreeing on everything and speaking in the same voice would get boring pretty quickly – but according to Sarkeesian, Rogan’s way is just another “rabbit hole.”