Few things ring quite as Orwellian as saying something is “legal but harmful” – and for that reason, needs to be censored, by law.

And if he were around, George Orwell might have been mortified that it is his own country that is enshrining this particular policy into legal practice – specifically, through the upcoming Online Safety Bill.

On March 17, the UK’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport announced that the bill was introduced in parliament in order to approve what kinds of speech are “legal but harmful” and that online platforms will be forced to “tackle” – i.e., censor.

No assault on online speech is complete without attempts to undermine privacy and this one is no different.

While the UK government claims that the 225 page Online Safety Bill will “make the UK the safest place to go online,” the means to achieve this so-called safety include granting the government unprecedented censorship powers, deputizing Big Tech companies to carry out this censorship, requiring these tech companies to collect even more user data, and giving large media outlets special exemptions that aren’t afforded to regular UK citizens.

The bill is one of the biggest free speech and privacy threats in recent memory, giving Big Tech and the government unprecedented power over online discourse.

Here’s what you need to know about the Online Safety Bill:

It has vague and subjective censorship requirements

Most of the censorship requirements in the badly-written Online Safety Bill are based on the term “harm.” Not only is this term already vague but the bill ambiguously extends beyond the idea of physical harm to the realm of what it calls “psychological” harm.

As if the definitions are not far-reaching enough, it further demands that simply the “risk” or “potential” of harm is to be treated “in the same way as references to harm.”

The examples of harm that are listed in the bill are equally ambiguous – such as; when “individuals act in a way that results in harm to themselves or that increases the likelihood of harm to themselves.”

Another badly-worded and wide-ranging example includes; “where, as a result of the content, individuals do or say something to another individual that results in harm to that other individual or that increases the likelihood of such harm (including, but not limited to, where individuals act in such a way as a result of content that is related to that other individual’s characteristics or membership of a group).”

These unclear and far-reaching definitions not only trample over the free speech rights of the British public, but also make it impossible for platforms to determine how to comply with the bill. That’s because many posts could be considered harmful under such broad and flighty definitions, especially when combined with the postmodern idea that speech can be psychologically harmful and with increasing sections of the public that expect to be coddled.

Adding to the lack of clarity, just days before the final bill was published, the UK Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS) Secretary of State Nadine Dorries, one of the main proponents of the bill, has contradicted the bill’s own wording.

Dorries tried to defend the bill by saying those who fear that “the Government wants to ban legal content if it ‘upsets’ or ‘offends’ someone” have a “complete misunderstanding” of the bill.

Dorries even tried to argue that some of the bill’s provisions would actually reduce the risk of platforms being pressured into removing legal content by activists “who claim that controversial content causes them psychological harm.”

However, in the era of safe spaces, the vague definitions leave the notion of determining psychological harm open to wide interpretation, likely causing platforms to play it safe and over-censor speech to avoid facing the whims of whichever government is in power.

This lack of clarity around the definition of harm also extends beyond the censorship requirements in the bill. There are two new criminal offenses in the Online Safety Bill that reference this term – a “harmful communications offence” and a “false communications offence.”

The harmful communications offense defines harm as “psychological harm amounting to at least serious distress” and describes a harmful communication as intentionally sending a message to “cause harm to a likely audience,” – ominously adding; when there’s “no reasonable excuse.”

It comes with a maximum penalty of two years in prison.

The false communications offense describes a false communication as sending a message that contains “information that the person knows to be false” with the intention of causing “non-trivial psychological or physical harm to a likely audience” when there’s “no reasonable excuse.”

It comes with a maximum penalty of 51 weeks in prison.

The UK’s police forces are already internationally infamous for using another vague and subjective term, “hate,” to justify adding people’s podcasts and tweets to their register of over 120,000 “non-crime hate incidents.” And with these new criminal offenses outlined in the bill, the police would have the power to arrest and charge UK citizens who are accused of causing someone “psychological harm” with speech that would be legal if it was communicated offline.

It gives the UK government increased censorship powers

The Online Safety Bill gives the Secretary of State and the UK’s communications regulator, the Office of Communications (Ofcom), sweeping new powers to dictate what people are allowed to say.

The bill gives the Culture Secretary the power to decide on and designate “priority content that is harmful.”

Once the Secretary of State has designated this content, social media platforms and search engines that fall under the scope of the bill’s regulations have to “use proportionate systems and processes” to prevent children from encountering this priority content.

These platforms are also required to specify in their terms of service how they’ll tackle priority content that’s deemed to be “harmful to adults” and apply these measures consistently.

Additionally, the Culture Secretary gets the power to decide the user number and feature thresholds that determine whether a company falls under the scope of these requirements to remove and tackle priority content.

Collectively, these provisions give the Culture Secretary unprecedentedly broad powers to not only choose the types of speech that is allowed but to also set the rules around which platforms have to censor content.

Under the bill, Ofcom will be granted the power to issue harsh punishments to platforms that fail to meet the Secretary’s censorship demands.

These punishments include applying for court orders that restrict access to platforms in the UK and fining platforms up to £18 million ($23.78 million) or 10% of their revenue (whichever is higher).

In another authoritarian turn, if Ofcom decides that a platform is failing to comply with any aspect of the Online Safety Bill, it can also demand information from the platform via an “information notice” and require the platform to name a senior manager who can be fined or imprisoned for up to two years if they’re found guilty of failing to comply with the requirements.

The grounds that determine whether a senior manager is guilty are as broad and far-reaching as the rest of the bill. Ironically, they include being “reckless” as to whether the information they hand over is false and handing over encrypted information with the intention “to prevent OFCOM from understanding such information.”

These Ofcom powers to punish platforms and potentially jail senior managers create a strong incentive for platforms to fall in line with the Secretary of State’s censorship demands. However, Ofcom also has other powers under the Online Safety Bill that it can wield to directly or indirectly push platforms to censor.

Ofcom can require platforms to take further steps to remedy their “failure to comply” and these steps can include requiring the use of “proactive” content moderation, user profiling, or privacy-invasive behavior identification technology, incentivizing platforms to collect even more data on users.

Even if Ofcom doesn’t directly require platforms to take additional steps, the Online Safety Bill grants it other powers that can be used to make life difficult for platforms that aren’t deemed to be meeting the government’s censorship demands.

Following the playbook of the Chinese Communist Party censors, these powers include the ability to enter and inspect a platform’s premises without a warrant, perform audits, demand documents and interviews, and compel platforms to appoint a “skilled person” that has to provide Ofcom with reports about “relevant matters.”

In a nod to George Orwell’s idea of the Ministry of Truth, the Online Safety Bill requires Ofcom to set up an “advisory committee on disinformation and misinformation.”

This committee will advise Ofcom on “how providers of regulated services should deal with disinformation and misinformation” and how Ofcom can exercise its powers under the Communications Act “in relation to countering disinformation and misinformation on regulated services.”

Not only does the Online Safety Bill give unprecedented censorship powers to government departments that voters have no direct influence over but some of these powers can be exercised with limited Parliamentary scrutiny.

For example, the Secretary of State can lay regulations for harmful content for up to 28 days without any Parliamentary approval and the Secretary of State’s power to designate priority content that is harmful will be set out in secondary legislation that reportedly requires less scrutiny from Members of Parliament (MPs) than the main bill.

Additionally, the codes of practice issued by Ofcom are laid before Parliament but get approved by default after 40 days.

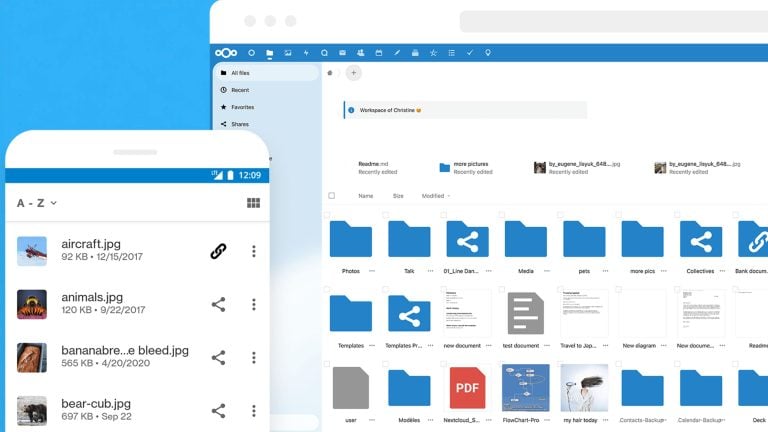

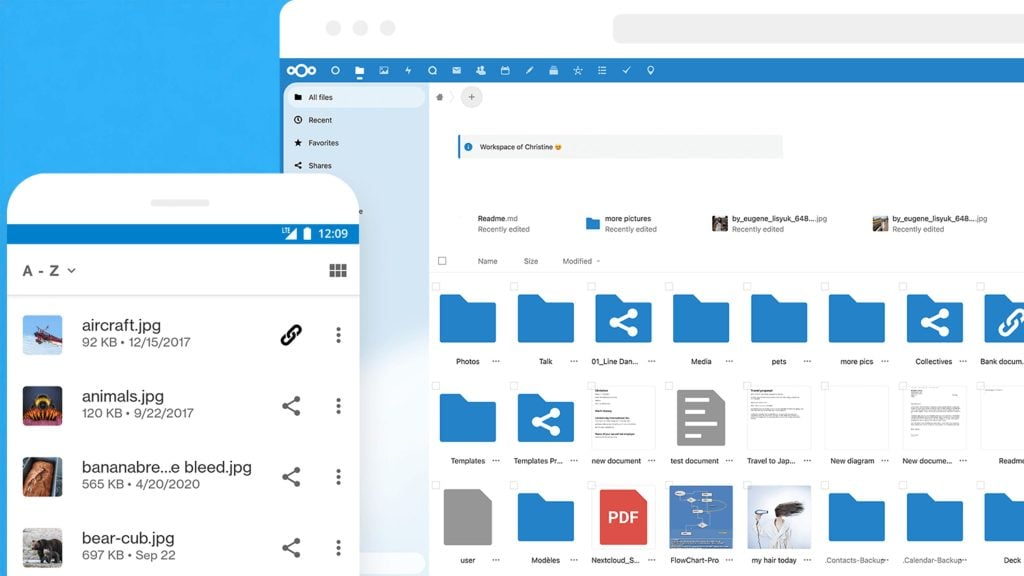

It deputizes Big Tech to enforce the law

While the provisions in the Online Safety Bill that allow the police to arrest and charge people for their online posts are chilling, the UK justice system does at least guarantee citizens the right to a fair trial and the right to appeal. These guarantees also apply to all civil offenses where there’s no threat of prison time.

However, many of the other provisions in the Online Safety Bill skip the police and the courts entirely and instead require the tech giants, some of which are monopolies, to act as enforcers of speech.

The Online Safety Bill deputizes Big Tech to seek out and prevent their users from encountering “illegal” and “fraudulent” content without any oversight from the police or the courts. This gives these powerful tech platforms the freedom to brand something illegal or fraudulent without any of the checks and balances of the justice system.

The bill also gives these tech giants additional powers that aren’t granted to police and the courts, such as the power to set their own rules around how they’ll deal with harmful content. All they have to do is state how they’ll tackle harmful content in their terms of service and then apply these provisions in their terms consistently.

These Big Tech companies already censor millions of posts each year for supposedly being harmful. With their additional powers and the threats of punishment in the Online Safety Bill, the number of censored posts is likely to be even higher if the bill comes into force.

Although the Online Safety Bill does require platforms to give users the right to appeal content takedowns, these appeals are far more centralized than the right to appeal a UK judicial decision. Under the UK justice system, citizens have the right to appeal decisions and have them reviewed by independent judges. Under the Online Safety Bill, citizens have to appeal to the tech companies that took down their content.

By deputizing Big Tech, the Online Safety Bill also creates a dystopian censorship alliance between these powerful companies and the UK government. The government can dictate its censorship requirements directly to its Big Tech enforcers without the police gathering any evidence of an alleged offense and without prosecutors gaining a conviction in a court of law or even a court order.

It mandates the implementation of identity and age verification technology

The Online Safety Bill mandates that services containing pornographic content implement age verification technology and use it to ensure that children “are not normally able to encounter” pornographic content.

Large platforms are also required to “offer all adult users of the service the option to verify their identity” (even if identity verification isn’t required to access the service) so that these users can choose to filter out “non-verified users.”

As a result, Big Tech companies, that already hold lots of personal data on their users, are now legally required to offer yet another channel through which they or their partners can scoop up even more personal and highly sensitive data.

This mandated implementation of identity and age verification technology also creates another data honeypot during a time when the number of data breaches and hacks have reached never-before-seen highs.

It contains carve outs only for large media outlets

One of the UK government’s main talking points when pushing the Online Safety Bill has been that “news content will be completely exempt from any regulation under the Bill.” However, the rules that govern these exemptions are written in a way that favors large media outlets and makes it difficult for small, independent outlets to qualify.

For starters, the state-funded media outlets the BBC and Sianel Pedwar Cymru (S4C) automatically qualify as “recognised news publishers” – the standard that determines whether a publisher is exempt from the bill’s regulations.

Other outlets need to either hold a license under the Broadcasting Act 1990 or 1996 or meet numerous conditions which include “publishing news-related material that is created by different persons,” having a registered office or business address in the UK, making the name and address of the outlet’s owner public, being subject to a standards code and editorial control, and having a complaints procedure.

Obtaining a license under the Broadcasting Act 1990 or 1996 creates additional costs for small outlets, such as the £2,500 ($3,300) license application fee and the minimum annual license fee of £1,000, ($1,320). It also gives Ofcom the power to decide which outlets can get a license.

The provision for news-related materials from non-license holders to be created by “different persons” also prevents individual journalists from qualifying as recognized news publishers. Furthermore, the requirement for non-license holders to make their name and address public shuts out anonymous or pseudonymous publishers from these recognized news publisher exemptions.

Additionally, these non-license holder conditions create additional compliance burdens which disproportionately impact smaller news outlets with fewer staff and resources.

It has laughable free speech and privacy protections

UK Culture Secretary Dorries has responded to criticism that the Online Safety Bill is “a censor’s charter” by pointing to the bill’s “duties to protect free speech.” However, these duties and the duties for platforms to protect user privacy are so weak that they have no impact when platforms comply with the bill’s obligations to tackle harmful content.

The bill pays lip-service to the idea that platforms should “have regard” to the importance of “protecting users’ right to freedom of expression within the law” and that they should be “protecting users from a breach of any statutory provision or rule of law concerning privacy.”

But if platforms comply with these over-reaching obligations to tackle this so-called “harmful but legal” speech as outlined in the bill, they will, by default, be at odds with the idea of protecting speech rights and privacy.

The bill itself is the biggest threat to free speech and privacy in living memory and Big Tech platforms have no history of protecting either.

Provisions for privacy should not mean social media monopolists acting as a guardian of user privacy; they should be in place to protect citizens’ data from the platforms themselves.

It disproportionately impacts smaller platforms

Dorries has tried to defend the Online Safety Bill by claiming that controversial obligations in the bill, such as the requirement to tackle “legal but harmful” content, only apply to “the biggest platforms.” However, the bill’s sweeping terms ensure that most social media platforms and search engines, regardless of their size, are subject to some of its requirements.

“User-to-user” services (internet services where content can be generated, uploaded, or shared) and “search” services (internet services that include a search engine) fall under the scope of the bill’s requirements if they have a significant number of UK users, have the UK as one of their target markets, or are capable of being used in the UK and “there are reasonable grounds to believe that there is a material risk of significant harm to individuals in the United Kingdom” presented by user-generated content or search content.

Since the definition of harm in the Online Safety Bill is so vague, the final requirement could be applied to almost any social media platform or search engine that can be accessed in the UK.

The only exemptions are services or parts of a service that enable emails, SMS and MMS messages, one-to-one live aural communications, and content where the function is to identify a user of an internet service (such as usernames and profile pics).

All of the platforms that fall under the scope of these requirements have to prevent their users from encountering illegal content and are subject to extensive auditing and reporting requirements.

Platforms that are likely to be accessed by children are subject to additional requirements which include preventing children from encountering certain types of harmful content and protecting children “judged to be at risk of harm from other content that is harmful to children.”

The only way for a platform to conclude that it isn’t likely to be accessed by children and avoid these additional requirements is to implement age verification technology that blocks children from accessing the service, prove that the service isn’t used by a significant number of children, or prove that the service isn’t likely to attract a significant number of users who are children.

The bill doesn’t specify how platforms should go about proving these metrics. However, since they’re all contingent on determining or predicting user age, using age verification technology would seemingly be the only viable option – causing users to have to hand over more data to platforms and preventing them from being able to communicate anonymously.

For smaller platforms, the cost of hiring the staff and investing in the technology that’s required to meet these obligations is significant and could even be so high that it prevents them from continuing to operate. By contrast, Big Tech platforms with multi-billion profits can easily absorb the additional compliance costs and the bill cements the power of the monopolists that have already gained dominance.

The bill’s proposals are at odds with the Conservative Party’s touted principles of supporting small businesses and maintaining a free market, in a world where the UK’s tech industry has already faltered due to stricter regulation and handed over most control to US-based platforms.

While smaller platforms are less likely to be impacted by the Online Safety Bill’s strictest obligations, it is possible. The user number and feature thresholds that determine this have yet to be set, will be outlined by the Secretary of State, and can be changed at any time.

If the Secretary of State sets a low user number threshold or names a feature that’s used by most platforms in these thresholds (such as recommendation algorithms), smaller platforms would be subject to the full requirements of the bill.

These full requirements include obligations for platforms to detail how they’ll deal with certain types of harmful content in their terms of service and then apply these measures consistently, prevent users from encountering “fraudulent advertising,” allow adults to “increase their control over harmful content,” allow adults to “filter out-non-verified users,” implement age verification and identity verification technology, and more.

If smaller platforms were swept up under these full requirements, the cost of compliance would likely be so great that it wouldn’t be worthwhile to continue.

The Online Safety Bill’s fines and fees are another area that have a disproportionate impact on smaller platforms. The maximum fine for non-compliance, up to £18 million or 10% of revenue (whichever is higher) is likely to be far greater than 10% of a small platform’s revenue. And while the fees have yet to be set, unless there’s an exemption for small platforms, the additional cost of paying fees will have a greater impact on smaller platforms with significantly less revenue than the tech giants.

Crushing free speech in the name of “safety”

UK rights groups and proponents have been almost unanimous in their criticism of the Online Safety Bill.

Mark Johnson, Legal and Policy Officer at civil liberties group Big Brother Watch, said: “This is a censor’s charter that will give state backing to big tech censorship on a scale that we have never seen before.”

Matthew Lesh, Head of Public Policy at the think tank Institute of Economic Affairs, described the bill’s threats to imprison tech executives as “eerily similar to how Russia and other authoritarian countries are currently behaving” and warned that it’s “an attack on free speech and entrepreneurialism.”

An impact assessment published last year estimated that the expected total cost of the bill will be a staggering £2.1 billion ($2.77 billion).

We obtained a copy of the full Online Safety Bill for you here.

The bill is currently making its way through Parliament and you can track its progress here.