The Department of Homeland Security has introduced a new rule that will greatly expand biometric tracking at US borders, establishing a system to photograph and identify every non-citizen who enters or leaves the country.

Although the regulation applies to non-citizens, the cameras do not distinguish citizens from non-citizens in real time.

CBP says US citizens may opt out by presenting their passports manually, and that photos of citizens are deleted within twelve hours once nationality is confirmed. However, that’s after the fact.

Starting December 26, Customs and Border Protection will have authority to take photographs of “all aliens” not only at airports and land crossings but at “any other point of departure” the agency designates.

We obtained a copy of the rule for you here.

DHS describes the change as “operational modernization.”

Privacy and civil-liberties organizations see it differently, warning that it formalizes a broad surveillance network that has been years in development.

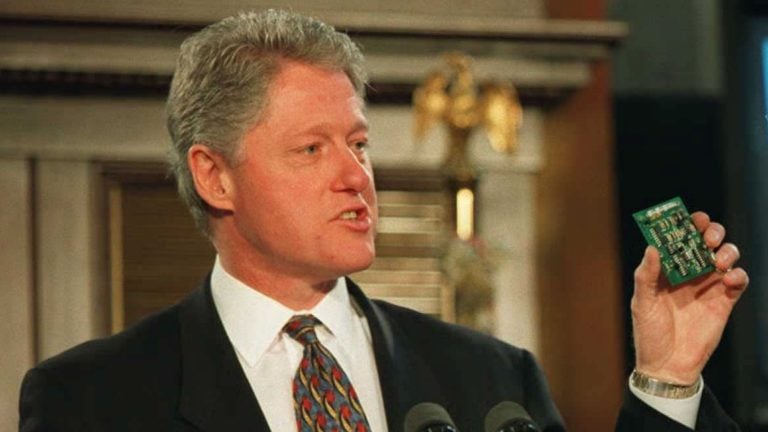

The policy completes the long-promised “biometric entry-exit” system that Congress first ordered in the 1990s and that gained renewed political momentum after the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001.

Related: TSA Fast Track Programs Are a Deal With The Devil

Earlier restrictions, such as pilot site caps and age-based exemptions, have been removed. The result is a regulation that opens the way for a connected web of facial-recognition systems across airports, seaports, vehicle lanes, and pedestrian crossings.

Until now, CBP’s use of biometrics has been uneven.

The “Simplified Arrival” program already photographs nearly all foreign travelers entering the country at major airports, comparing the images to visa and passport records.

Departures, however, were rarely monitored except at a few test sites. The new rule changes that by requiring biometric collection for every non-citizen departure, by air, land, or sea.

Officials claim the expansion will make travel faster and safer. DHS says “photographing travelers at entry and exit allows CBP to verify identities within seconds, reducing document fraud and streamlining inspections.”

Each image is sent to the Traveler Verification Service, a cloud-based matching system that connects with other government databases. When the software confirms a match, it notifies a CBP officer.

For non-citizens, the photos and related data can be retained for as long as seventy-five years in the central biometric database known as IDENT.

The rule gives DHS wide flexibility to decide where and when to take photographs, allowing cameras anywhere CBP operates, including boarding gates, border checkpoints, cruise terminals, and even private airfields or marinas.

Related: Quiet Skies Turns Dark as Senate Exposes Secret Surveillance of Americans

Officials justify the scope as a way to prevent travelers from leaving unverified, while privacy advocates argue it effectively enables biometric surveillance at almost any international departure point and impacts citizens, too.

False matches remain a concern. CBP testing found error rates of up to three percent, which could mean thousands of travelers are misidentified each day once the system reaches nationwide scale.

Such errors make voluntary participation questionable, since a mistake can result in data being retained beyond the promised deletion window.

The traveler verification system connects with other DHS databases, including the Automated Targeting System, the Arrival and Departure Information System, and Enhanced Passenger Processing.

Data ultimately feeds into IDENT, which stores fingerprints, facial scans, and iris data.

Non-immigrant records can be held for seventy-five years, permanent resident data for fifteen, and US citizen records only in short-term logs.

Privacy and technology groups have warned that the program’s long retention periods and interagency data sharing could turn it into a persistent tracking tool for millions of lawful residents and visa holders.

The problem is that convenience and automation can create coercive conditions over time.

When facial recognition lanes move passengers through in seconds while manual verification takes several minutes, those who opt out will find themselves in slower, longer, less-staffed lines.

Airports, pressured to maintain throughput, will likely allocate fewer agents to manual document checks, effectively penalizing those who choose not to participate in biometric programs.

This subtly transforms a “voluntary” system into a de facto mandatory one. The slow erosion of choice doesn’t come from a formal mandate but from bureaucratic efficiency pressures and traveler frustration.