The story starts with a tweet that barely registered on the internet. A few hundred views, a handful of likes, and the kind of blunt libertarian framing that is common on X every hour of every day.

Yet in Germany, that tiny post triggered a 6am police raid, a forced phone handover, biometric collection, and a warning that the author was now under surveillance.

The thing to understand is that this story only makes sense once you see the sequence of events in order.

The story goes like this:

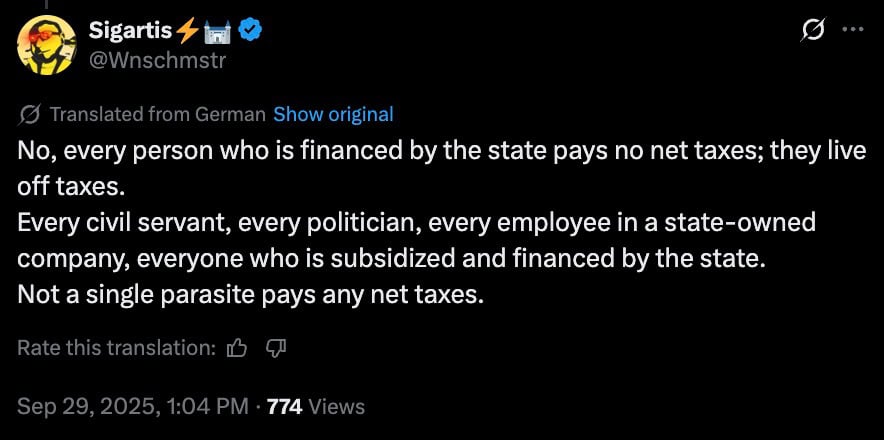

- A man in Germany, known publicly only as Damian N., posts a short comment on X, calling government-funded workers “parasites.”

- The post is tiny. At the time he was raided, it had roughly a hundred views. Even now, it has only a few hundred.

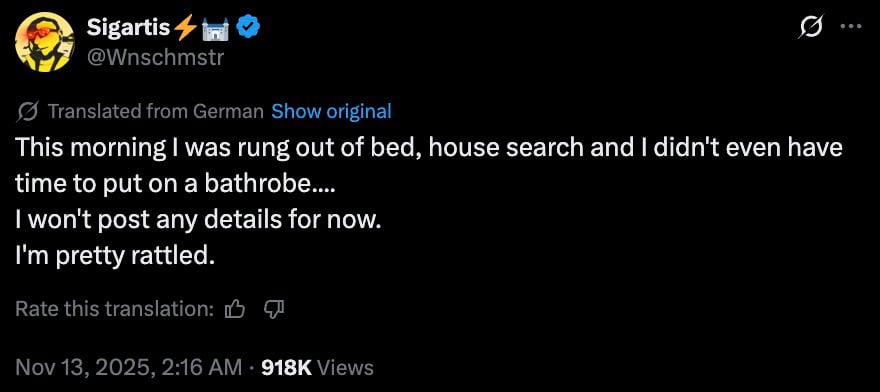

- Despite the post’s obscurity, police arrive at Damian’s home at six in the morning.

- He says they did not show him the warrant and did not leave documentation of what they seized.

- Police pressured him to unlock his phone, confiscated it, took photos, fingerprints, and other biometric data, and even requested a blood sample for DNA.

- One officer reportedly warned him to “think about what you post in the future” and said he is now “under surveillance.”

- The entire action was justified under Section 130 of the German Criminal Code, which is meant to prohibit inciting hatred against protected groups.

- Government employees are not such a group, which makes the legal theory tenuous at best.

- Damian’s lawyer says the identification procedures and possibly the raid itself were illegal.

That is the sequence. A low-visibility political insult becomes a criminal investigation involving home searches, device seizure, and biometric collection.

The thing to understand is that this is not about one man’s post. It is about a bureaucracy that treats speech as something to manage and a set of enforcement structures that expand to fill the space they are given.

Start with the enforcement context. Germany has built a sprawling ecosystem around “online hate”: specialized prosecutor units, NGO tip lines, and automated scanning for taboo keywords.

The model is compliance first and legal theory second.

Once you create an apparatus like this, it behaves the way bureaucracies behave. It looks for work. It justifies resources by producing cases. A tiny X post with inflammatory language becomes a target because it contains the right keyword, not because it has societal impact.

Police behavior fits the same pattern. Confiscating phones is strategically useful because it imposes real pain without requiring a conviction.

Even prosecutors have said that losing a smartphone is often worse than the fine.

Early-morning raids create psychological pressure. Collecting biometrics raises the stakes further. None of this is about public safety. It is about creating friction for saying the wrong thing.

The legal mismatch is the tell. Section 130 protects groups defined by national, racial, religious, or ethnic identity.

There is also the privacy angle, which becomes impossible to ignore. Device access, biometrics, DNA requests: these are investigative tools built for serious crimes.

Deploying them against minor online speech means the line between public-safety policing and opinion policing has already been crossed. Once a state normalizes surveillance as a response to expression, the hard part becomes restoring restraint.

It is a deterrence strategy, not a justice strategy. And it reinforces why free speech and strong privacy protections matter. Without them, minor speech becomes an invitation for major intrusion.

The counterintuitive part is that the smallness of the post makes a raid more likely, not less.

High-profile content generates scrutiny and political costs. Low-profile content discovered through automated or NGO-driven monitoring is frictionless to act on. Unless people are reading Reclaim The Net, most people never hear of these smaller cases.

Looking ahead, the pressure will only increase. As more speech moves to global platforms that are harder to influence, local governments will lean more heavily on domestic law enforcement as their lever of control.

That means more investigations that hinge on broad interpretations of old statutes and more friction between individual rights and bureaucratic incentives.

This is particularly true in Germany and places like the UK, where the government doesn’t seem to feel any shame about raiding its citizens over online posts.