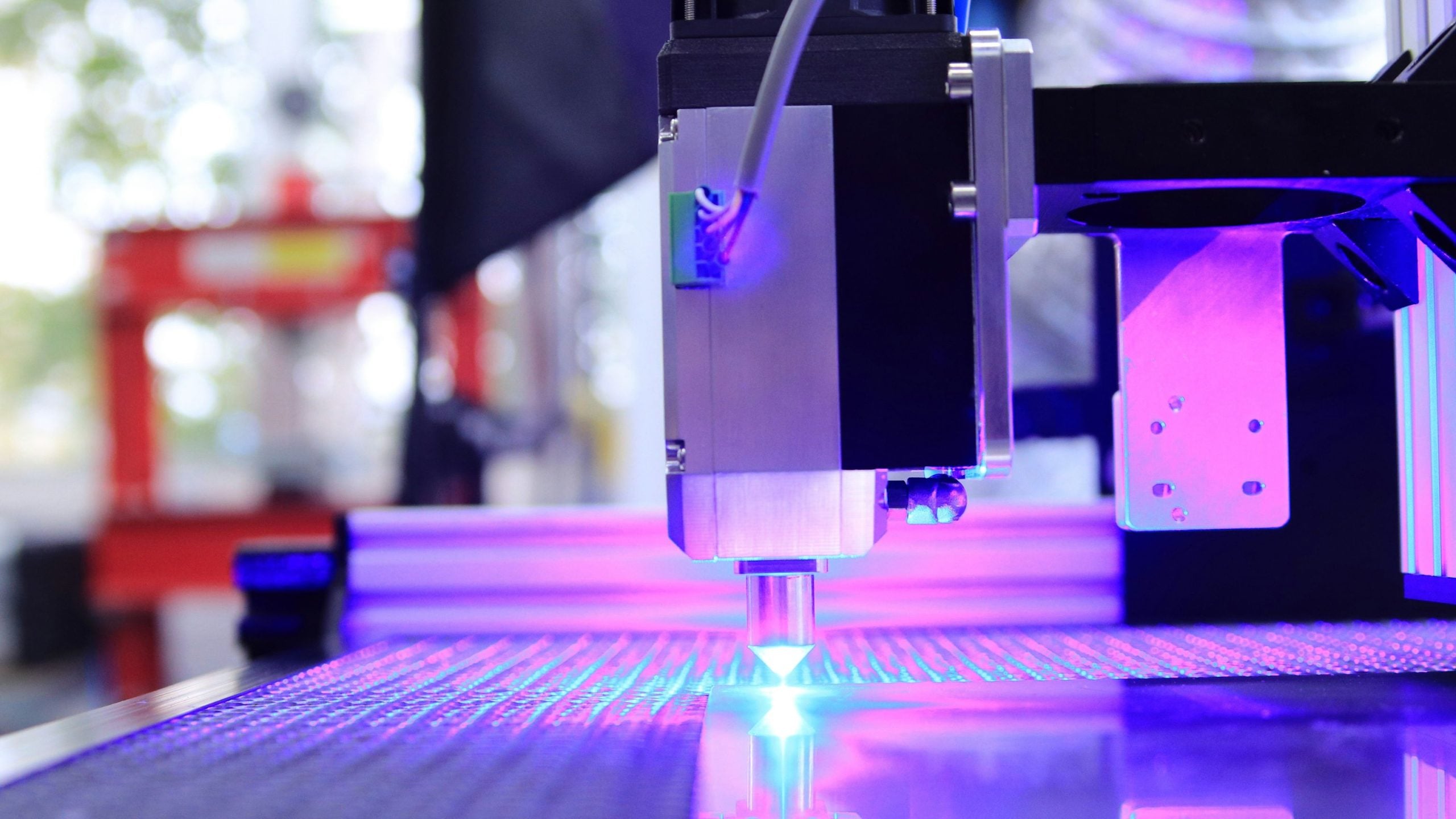

Washington lawmakers are advancing two proposals that would expand the state’s control over how 3D printers and similar equipment can be used, citing the spread of untraceable firearms as justification.

The measures have raised concern among those who see them as an overreach that risks curbing lawful innovation and digital design freedoms.

House Bill 2321 would require that all 3D printers sold in Washington after July 1, 2027, include built-in safeguards that detect and block attempts to produce firearms or firearm components.

We obtained a copy of the bill for you here.

The measure defines these safeguards as “a firearms blueprint detection algorithm,” which must be able to reject such print requests “with a high degree of reliability” and prevent users from disabling or bypassing the control system.

To meet the new rule, manufacturers could either embed the detection algorithm directly in a printer’s firmware, integrate it through preprint software, or use an authentication process that screens design files before printing.

Companies that fail to comply could be charged with a class C felony, facing penalties of up to five years in prison and a $15,000 fine.

A related bill, House Bill 2320, would prohibit the use of 3D printers, CNC milling machines, or other tools to produce unregistered firearms.

It would also make it illegal to distribute or possess digital files capable of creating gun parts.

The bill targets both the physical manufacturing of ghost guns and the online exchange of design data used to make them.

Representative Osman Salahuddin, who introduced the legislation, said it is meant to close a dangerous gap in state law. “With a 3D printer that costs a few hundred and a digital file that can be downloaded online, someone can now manufacture an untraceable firearm at home,” he said. “No background check, no serial number, and no accountability.”

The main problem with all of this is that the algorithm must be built so it cannot be bypassed by a technically skilled user, effectively outlawing the ability to modify a device’s firmware or gain root access to it. In short, tinkering with your own hardware could be treated as a criminal act.

Once that model is codified in law, manufacturers would gain a powerful excuse to roll out closed systems that require server authentication or proprietary software to function.

The 3D printer would no longer be a tool you own; it would become a managed service, dependent on the company’s servers and subject to its terms.

When the server is shut down or the software license expires, the device could simply stop working. There are no provisions in the bill to guarantee continued functionality or support when the manufacturer moves on.

This kind of policy invites the same behavior already seen in other industries: forced obsolescence disguised as security. Consumers have watched other “smart” devices turn useless when companies went bankrupt or changed their business models.

Embedding mandatory authentication systems into 3D printers guarantees that the same pattern will repeat, except this time, companies can claim they are acting under government mandate.

It also poses serious legal and practical problems. Many 3D printers rely on open-source firmware governed by licenses that explicitly permit modification.

Mandating that these systems must include unremovable restrictions directly conflicts with those licenses and makes compliance impossible.

The bill’s vague definition of “three-dimensional printer” even extends to CNC mills, lathes, and other fabrication tools, threatening far more than just hobbyist printers.

The legislation gives the state’s attorney general broad authority to expand what must be blocked in the future, without requiring further legislative approval.

That creates a moving target, where new categories of restricted designs could be added at any time, leaving both users and manufacturers scrambling to comply.

Supporters of the bill frame it as a matter of public safety, but the mechanism it creates, mandatory, remote-controlled restriction systems, would normalize the idea that ownership of physical devices is conditional.

It would turn open hardware into closed platforms and give manufacturers a built-in justification to lock down, disable, or replace products at will.

The real question is not whether people should be allowed to 3D print guns; it is whether the state should empower corporations to decide what a person is allowed to do with their own machine.

The structure of this law would make permanent the shift from ownership to permission, one firmware update at a time.