Picture the scene: a Bentley Bentayga, price tag somewhere north of what most people owe in student loans, idling in the Folkestone tunnel terminal, preparing to whisk its driver, one of the nation’s most prominent political activists and political migraine for Keir Starmer’s government, Tommy Robinson, off to sunny Spain.

You’d expect smugglers of luxury goods, maybe. Or a footballer.

Instead, it’s Robinson, who found himself staring down the barrel of Britain’s counter-terrorism laws, not because he had explosives or an AK-47 stashed under the seat, but because he refused to give the police his iPhone passcode.

Yes, that’s right. In a country where burglary barely gets a police visit unless the thief leaves behind a business card and a selfie, Kent’s finest deployed the full blunt force of the Terrorism Act 2000…because a man in designer sunglasses said “not a chance, bruv” when they asked for his PIN.

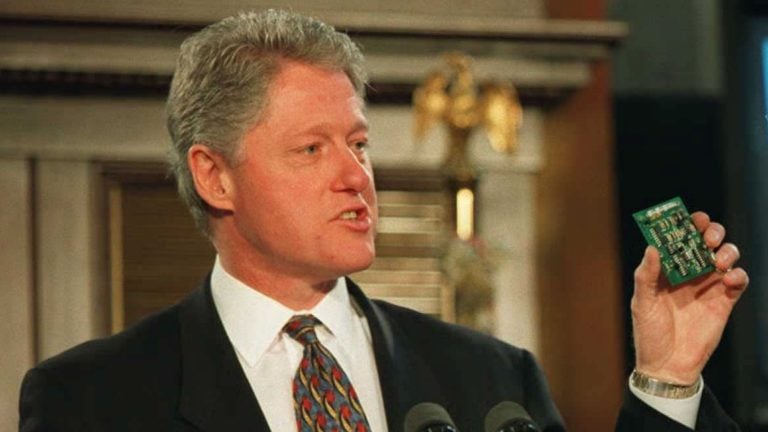

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the absurdity here. The legislation in question, Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act, was born in the year 2000, when Tony Blair was still selling Cool Britannia to the world and convincing Parliament to make temporary wartime powers a permanent lifestyle choice.

Back then, the idea was to keep Britain safe from people who blow up buses, not from activists in SUVs who are going on a trip to Benidorm.

Schedule 7 gave police the right to stop, interrogate, and detain anyone crossing a UK border, without needing so much as a whiff of suspicion.

Naturally, civil liberties groups kicked off, warning this kind of power would eventually be used not to stop terrorists, but to hassle people for thinking the wrong thoughts.

Now, to be clear, Robinson wasn’t being stopped because he had so much as a suspicious sandwich on him. Police claimed he gave “vague replies” about his travel plans and then demanded his phone PIN.

Robinson declined, in his own unique style, replying: “Not a chance, bruv…You look like cunts so you ain’t having it.”

He argued that his phone contained journalistic material and confidential information about grooming gang victims, an argument you’d think would be worth, at minimum, some caution from officers supposedly trained in the nuances of press freedom and data protection.

But no, out came the terrorism laws.

In the courtroom, things got even more farcical. Prosecutor Jo Morris stood up in court and did her best to give this house of cards some scaffolding.

According to her, the officers had grown “concerned” by Robinson’s “demeanor” the moment he wandered into the inspection area alone. This, apparently, was clue number one in the national security sudoku.

“He gave short, vague replies and made no eye contact,” she said, like Robinson was a polygraph test away from detonation.

So they whisked him off to an interview room, seized his phone, and along the way, he tried to film the moment. Officers told him to “relax.”

Relax? He’d just been pulled under terrorism legislation for not smiling enough and having the audacity to travel with a mobile phone.

But here’s where the whole operation unravelled.

The prosecution needed to prove that the police had acted with genuine concern for national security. That’s the entire point of Schedule 7. You don’t just get to stop someone because they make you feel a bit weird.

The defense called the stop what it plainly was: a fishing expedition. There was no MI5 alert, no suspicious email trail, no intercepted WhatsApp group. Just a Bentley, some cash, and the unmistakable scent of political targeting.

Yes, he had a lot of cash. Yes, he was driving a car that looked like it belonged in a Dubai sheikh’s driveway. But unless we’ve decided to classify Essex bachelorette parties and Premier League footballers as national security threats, those aren’t exactly cause to break out the anti-terror laws.

District Judge Sam Goozee, listened to the evidence, blinked slowly, and basically concluded that the police had stopped Robinson not because of any real security threat, but because they didn’t like his political beliefs.

“I cannot put out of my mind that it was actually what you stood for and your political beliefs that acted for the principal reason for this stop,” he said.

And there it was. The clattering of irony hitting the floor like a dropped truncheon.

A law built to protect Britain from violent terrorists was now being used to hassle people because of…their views.

***

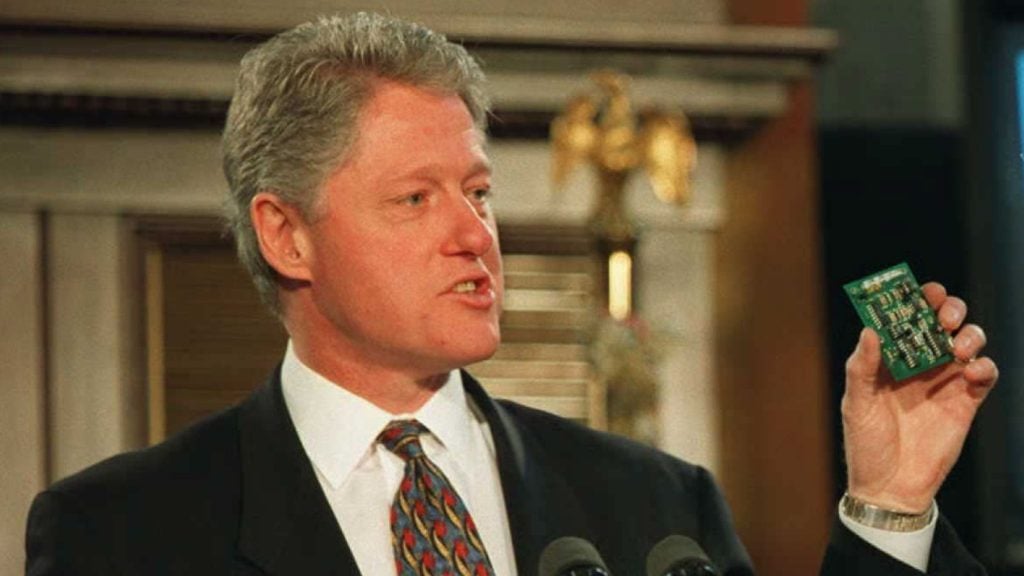

Once upon a time, your phone was just a thing to call your friends and accidentally download ringtones from dodgy numbers in the back of magazines.

Now, it’s a vault. Your conversations, your banking apps, your half-finished work emails, your therapist’s advice, your texts from 2017; all of it, piled into that small, glowing slab in your pocket.

For journalists, lawyers, campaigners, and anyone else with an extra reason to keep things confidential, it’s even more critical.

Sources. Legal privilege. Survivor testimonies. That’s why, historically, the state has needed actual legal grounds: warrants, oversight, tangible suspicion, to poke around inside. But Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act, in its wisdom, says: Nah, we’ll just take a look anyway.

That’s the problem. And that’s what made Judge Sam Goozee’s ruling in Robinson’s case so important, and not just for the man himself, who once again found himself being prosecuted not for doing something wrong, but for not playing ball with the whims of bureaucracy in hi-vis vests.

This was a victory for due process, yes, but also for something rarer these days: common sense. Because here’s the real issue: this case should never have reached court in the first place.

A man was prosecuted for refusing to unlock his phone. Not because he’d committed a crime. Not because he was linked to terrorism. But because he wouldn’t type a few digits into a screen for a police officer with a clipboard and a grudge who had no grounds.

That alone should scare the hell out of everyone.

It’s not just about Robinson. You could swap him for a Greenpeace organizer, a trade union representative, a man tweeting mean things about the government from his home’s Wi-FI. The precedent is what matters.

If the police can demand your phone access without a warrant, then your right to privacy isn’t a right, it’s a polite suggestion, revoked the moment you act suspiciously by, say, not making eye contact.

This fits neatly into a wider picture that ought to make the nation’s eyebrows permanently hover around the hairline. Facial recognition cameras are already blinking at people from main streets in London, Birmingham, and Leeds.

Meanwhile, despite the fact that authorities have proven to be untrustworthy when it comes to civil liberties, Prime Minister Keir Starmer is polishing off plans for a national digital ID system and backdoors into people’s iCloud accounts.

Together, these ideas form a cheery vision of a Britain where your face is logged, your data is centralized, your movements are tracked, and your phone is subject to inspection if you happen to raise an eyebrow at the wrong moment.