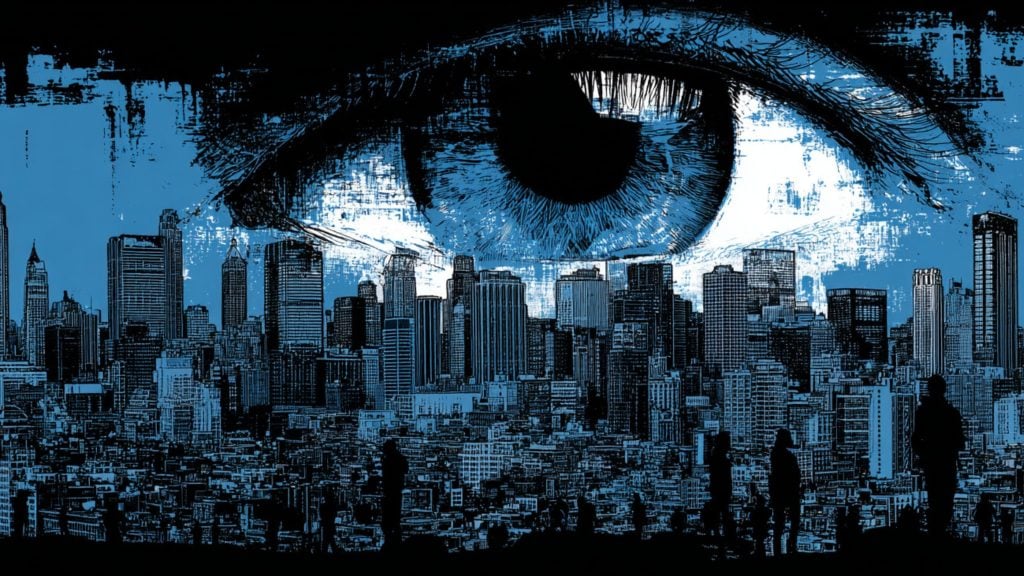

Google’s latest move to tighten control over the Android ecosystem is being met with sharp resistance from the open-source community.

Marc Prud’hommeaux, a member of the F-Droid board, has warned that the company’s proposal to require identity verification for all Android developers would effectively dismantle F-Droid.

He confirmed that the project is seeking regulatory review of the plan and urged both developers and users to press their governments to act before the policy takes effect.

Under the proposal, Android devices certified by Google would only accept apps registered by verified developers, even when sideloaded from outside the Play Store.

The rollout is set to begin next year. Google maintains that this system is needed to combat malware, claiming sideloaded apps carry “over 50 times more malware” than those obtained through its official marketplace.

According to the company, forcing developers to verify their identities would introduce accountability and shield users from fraud.

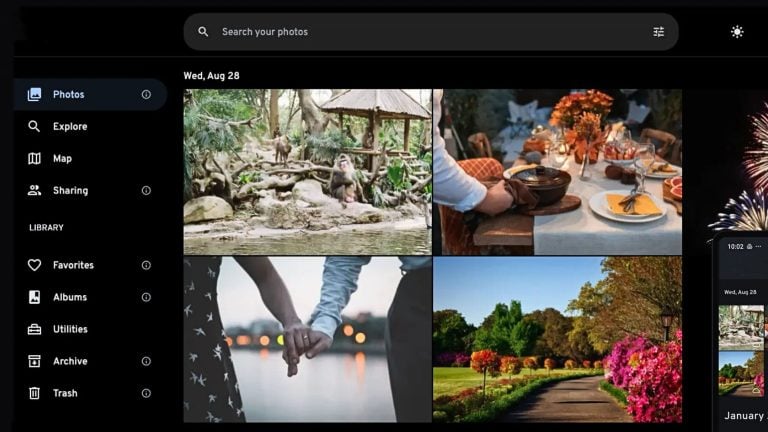

F-Droid operates on very different principles. The non-profit distributes only open-source software and has no user accounts, a design choice meant to prevent surveillance of its community.

More: Top 10 Must-Have F-Droid Apps for Privacy, Security, and Productivity

Its volunteer team builds apps from publicly available code, signs them with cryptographic keys, and warns users about unwanted elements such as advertising, proprietary components, or privacy risks.

Prud’hommeaux emphasized that these practices create a higher level of trust than Google’s own store, where malicious apps have been repeatedly discovered.

In a recent post, he made clear that the upcoming rules cannot be reconciled with F-Droid’s mission: “The F-Droid project cannot require that developers register their apps through Google, but at the same time, we cannot ‘take over’ the application identifiers for the open-source apps we distribute, as that would effectively seize exclusive distribution rights to those applications.”

He concluded that “If it were to be put into effect, the developer registration decree will end the F-Droid project and other free/open source app distribution sources as we know them today.”

For Prud’hommeaux, the issue goes beyond app distribution. He argues it is about user freedom itself: “Users should have the right to run whatever software they want on a computer they own.” His stance frames Google’s decision not as a safety upgrade but as an effort to centralize power over an ecosystem that was once advertised as open.

Although Android is technically built on the Linux-based Android Open Source Project, the system has steadily shifted under Google’s control.

Google Play Services is closed-source, and earlier this year, the company restricted AOSP development to a private branch, only occasionally publishing updates.

While much of the source code remains available under the Apache 2.0 license, the direction of the platform is increasingly dictated by Google alone.

The fate of F-Droid now hinges on whether regulators and political leaders are willing to challenge Google’s tightening grip. Without intervention, a policy framed as user protection could instead erase one of the few remaining routes for independent software on Android.