If you were looking for a tutorial in how not to govern, Nepal’s ruling class has generously offered a new lesson plan.

Step one: shut down social media because it makes you feel insecure. Step two: pretend the resulting nationwide meltdown is a fluke. Step three: watch your approval rating turn into a riot and your parliament building go up in flames.

What began as a bureaucratic tantrum over unregistered apps spiraled, almost immediately, into a full-blown generational uprising.

The uprising kicked off when Nepal’s Ministry of Communication had the bright idea to demand that social media companies register under new regulations, rules so vague they could have been written by someone trying to criminalize sarcasm.

When the platforms didn’t register, the state did what all cornered bureaucrats do: they pulled the plug.

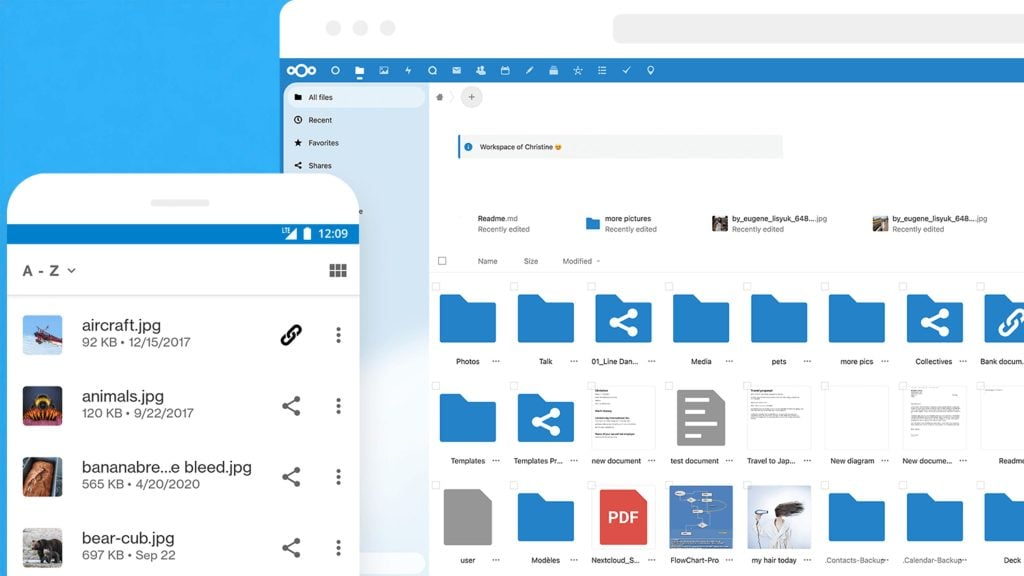

The geniuses in Kathmandu decided that banning Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and WeChat, because they would not censor, would somehow bring digital order to the country.

Instead, they triggered the kind of public explosion normally reserved for collapsing currencies or rigged elections.

It’s important to make clear that the social media blackout may have lit the match, but the country was already soaked in gasoline. For most of the people in the streets, the platform bans weren’t the whole problem. They were the final insult.

The real list of grievances reads like a greatest hits album of government failure. Start with corruption, a national tradition at this point. The 2017 Airbus deal, where Nepal Airlines managed to misplace $10.4 million in public funds without even delivering entertaining excuses, became a case study in how to lose money in government without really trying. No one went to jail. No one even got demoted. But the public remembered. They always do.

Then there is the economy, or what’s left of it. Officially, youth unemployment hit 20 percent in 2024. Unofficially, it’s worse, depending on how you define “employment” and whether you count selling SIM cards on a sidewalk as a career. One in every thirteen Nepalis works abroad just to keep their families from sinking, sending back enough remittances to prop up a government that thanks them with platitudes and zero policies.

For young people still stuck in Nepal, the message has been clear: there is no future here unless your dad is on a party committee. The government hasn’t so much failed to create jobs as it has outsourced hope entirely.

Add to that the political circus. Since 2008, when the monarchy was finally shelved, Nepal has cycled through 14 different governments. Not one of them finished a full term. The entire concept of political continuity in the country has been reduced to a punchline. Voters aren’t even surprised anymore. They just check the news to see who’s getting fired this week.

And when the people want to speak out and air their grievances, the government tries to censor the social media platforms. That was a big mistake.

By Tuesday morning, the government caved. Access to all 26 banned platforms has been restored. Officials framed it as a thoughtful policy revision. Everyone else recognized it for what it was: a full-speed backpedal from a policy that went up in smoke the moment it hit the street.

Nobody outside the ruling class was surprised when the blackout turned ugly. What was surprising was the speed and scale of the blowback. By Monday, Kathmandu looked like a city prepping for regime change. Crowds breached a security post near Parliament.

Witnesses described scenes of live ammunition mixed with rubber bullets and water cannons. At least 19 people are confirmed dead. Hundreds are injured. Emergency rooms are stacked. The situation is still active.

Eventually, someone in the cabinet remembered what year it was and realized cutting off Instagram might not be the win they thought it was.

And what exactly are these “demands”? According to the kids holding the line in the streets, it’s not just about the apps anymore.

They want resignations. Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli was at the top of the list, trailed closely by a conga line of officials accused of corruption and a fondness for authoritarian stunts.

The Prime Minister did resign, with no clear successor in place, shortly after his home was torched by protesters.

The outrage didn’t stay bottled up in Kathmandu, either. It spilled out across the country: Pokhara, Chitwan, Janakpur.

Nepali Congress MP Rajendra Bajgain finally emerged to deliver a soundbite: “If the Congress government cannot protect democracy, it must immediately step down.”

But among younger Nepalis, this wasn’t about party politics. This was about basic survival. Social media platforms aren’t luxuries; they’re oxygen. That’s how people earn, learn, and stay connected to relatives wiring home money from Qatar or Malaysia or wherever else Nepali labor is exported to keep the country’s GDP from flatlining.

So when the apps disappeared, so did a lifeline. WhatsApp storefronts went dark. Online tutors were suddenly out of business. Whole families lost touch. And the kids took it personally, because it was personal.

It’s economic sabotage. But it’s also something else: a class marker. Because the people making these decisions, funnily enough, aren’t the ones relying on WhatsApp to get paid or Messenger to call their mom abroad.

A solid chunk of those who charged the barricades on Monday were students who were still in class earlier that morning. Some probably still had homework due.

That’s the level of disillusionment the Nepali state has managed to achieve in an instant: students walking out of chemistry class to take on a censorship system their teachers are too scared to criticize.

Embassies from the US, France, and five other countries released a tidy joint statement reminding Nepal that free expression is still, technically, a thing.

And that brings us back to the big picture. Nepal, which once got a gold star for being the region’s plucky democratic experiment, was trying to join the regional authoritarian club, just without the efficiency.

Since abolishing its monarchy in 2008, the country has bounced between dysfunction and disillusionment like a pinball machine nobody wants to unplug.

This time, though, the government’s attempt to control the conversation detonated. The apps are back, sure. But trust? That’s still offline.

What started as censorship has ballooned into something larger: a hard look at who gets to decide how people live, speak, and survive.

The kids aren’t logging off. And the state, despite reconnecting the internet, may have finally disconnected from its last thread of legitimacy.