Over the past two weeks, internet users in Pakistan have watched their encrypted connections vanish one after another. Beginning December 22, 2025, major VPNs, including Proton VPN, NordVPN, ExpressVPN, Surfshark, Mullvad, Cloudflare WARP, and Psiphon have been systematically blocked across the country, according to Daily Pakistan.

The blackout follows a government licensing framework that, on paper, regulates VPN providers but in practice gives the state the power to decide which privacy tools are permitted.

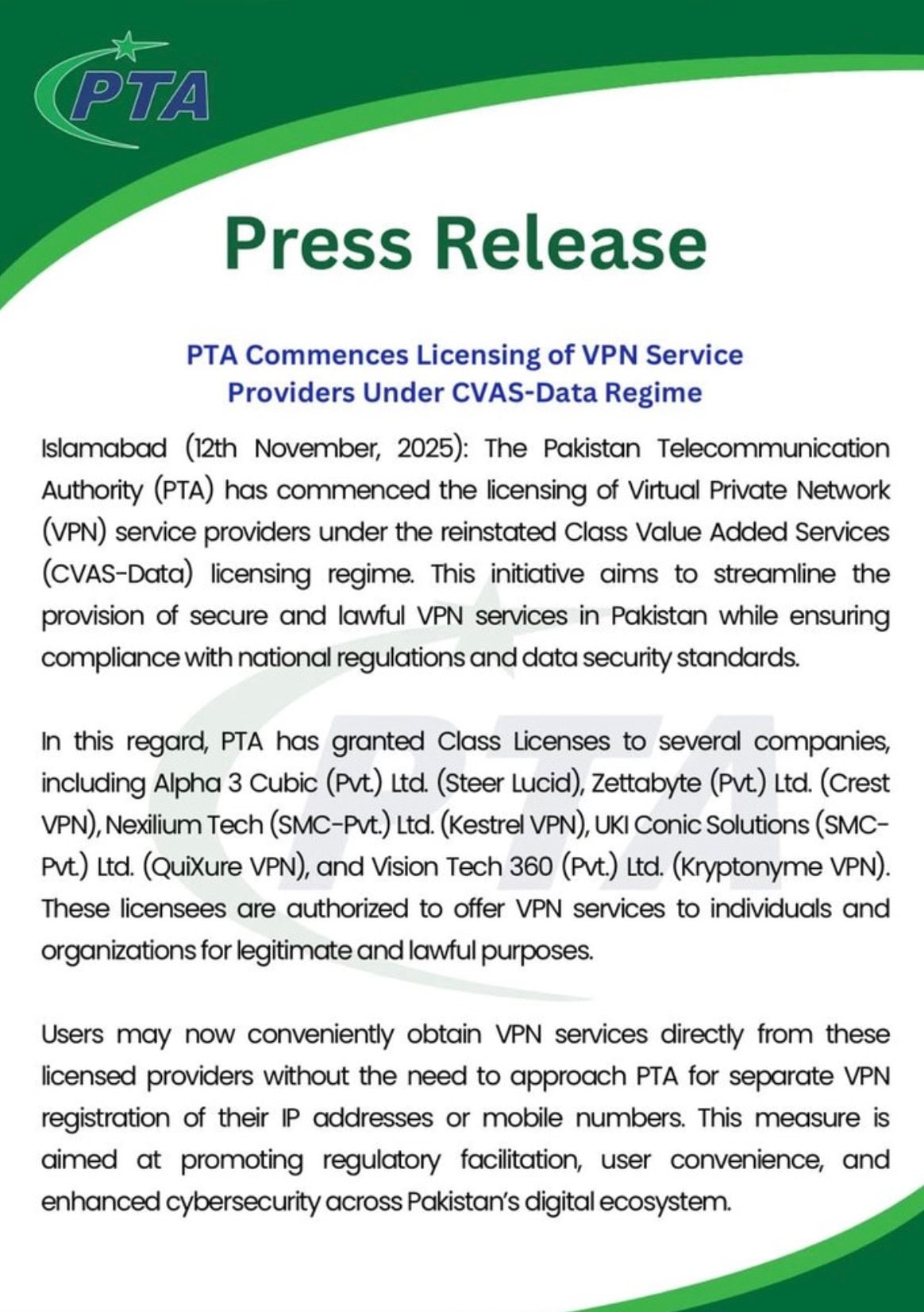

The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) began enforcing its Class Value Added Services (CVAS-Data) licensing rules in November 2025, nearly a year after quietly introducing the policy.

Under these regulations, companies that want to operate legally must install “Legal Interception” compliant hardware and hand it over “to nationally authorized security organizations” at their own expense whenever instructed.

Any VPN not listed as licensed is automatically subject to blocking by domestic internet providers.

The bans have not silenced everyone. Some VPNs like Proton have a “Stealth” protocol, Mullvad VPN has a QUIC & WireGuard Obfuscation, and IVPN has V2Ray and Obfsproxy Obfuscation, which can be turned on, helping people bypass some of the VPN blocking attempts.

Officials have promoted the licensing regime as a modernization effort, describing it as a step toward “regulatory facilitation, user convenience, and enhanced cybersecurity across Pakistan’s digital ecosystem.”

In mid-November, the PTA announced that five domestic firms had already been authorized to provide what it called “secure and lawful” VPN services.

The state’s rhetoric masks a deeper problem. Under this model, privacy tools only exist with government permission.

By forcing providers to operate inside the country’s legal jurisdiction, regulators gain direct leverage over their infrastructure and data.

This is not a new battle. For years, authorities have tried to outlaw “unregistered” VPNs, only to face legal pushback and technical difficulties.

The licensing system sidesteps those obstacles by creating a closed market that pre-filters which VPNs may function at all.

Pakistan’s approach fits a larger pattern of tightening control over online space. Access to platforms like X has been disrupted repeatedly, and digital monitoring capacity has expanded with help from foreign technology suppliers.

A network of licensed VPNs fitted with interception equipment would plug directly into that architecture, ensuring that even encrypted traffic routes through systems capable of inspection.

The opposition Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), founded by former Prime Minister Imran Khan, denounced the government’s move, accusing the “dictatorial regime” of censorship.

The party has warned that the new restrictions further isolate Pakistanis from independent information sources at a time of deep political division.

Digital rights groups and business organizations have also raised alarms. Pakistan’s technology sector, particularly its freelance and software export industries, relies on stable and uncensored access to global services.

Previous attempts to curb VPN usage led to slow connections, disrupted client communication, and uncertainty for firms handling foreign contracts.