Typically, in the past, those charged with election suppression tactics have been public officials or those running for election. But now, for the first time, a Florida-based meme artist is facing up to a decade behind bars after being found guilty of conspiring to “deprive individuals of their right to vote in the 2016 presidential election.”

Douglass Mackey, a 33-year-old self-proclaimed “American nationalist” from West Palm Beach, was convicted in a Brooklyn federal court on Friday.

We obtained a copy of the ruling for you here.

Mackey, who went by the online moniker “Ricky Vaughn,” had a substantial following on Twitter, boasting around 58,000 followers at the height of his influence.

Mackey was frequently retweeted by then-presidential candidate Donald Trump.

Arrested in January 2021, Mackey’s sentencing is slated for August 16, with the potential for a ten-year prison sentence.

His attorney, Andrew Frisch, remains optimistic about their chances on appeal, stating that the 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals in Manhattan will have multiple reasons to vacate the conviction.

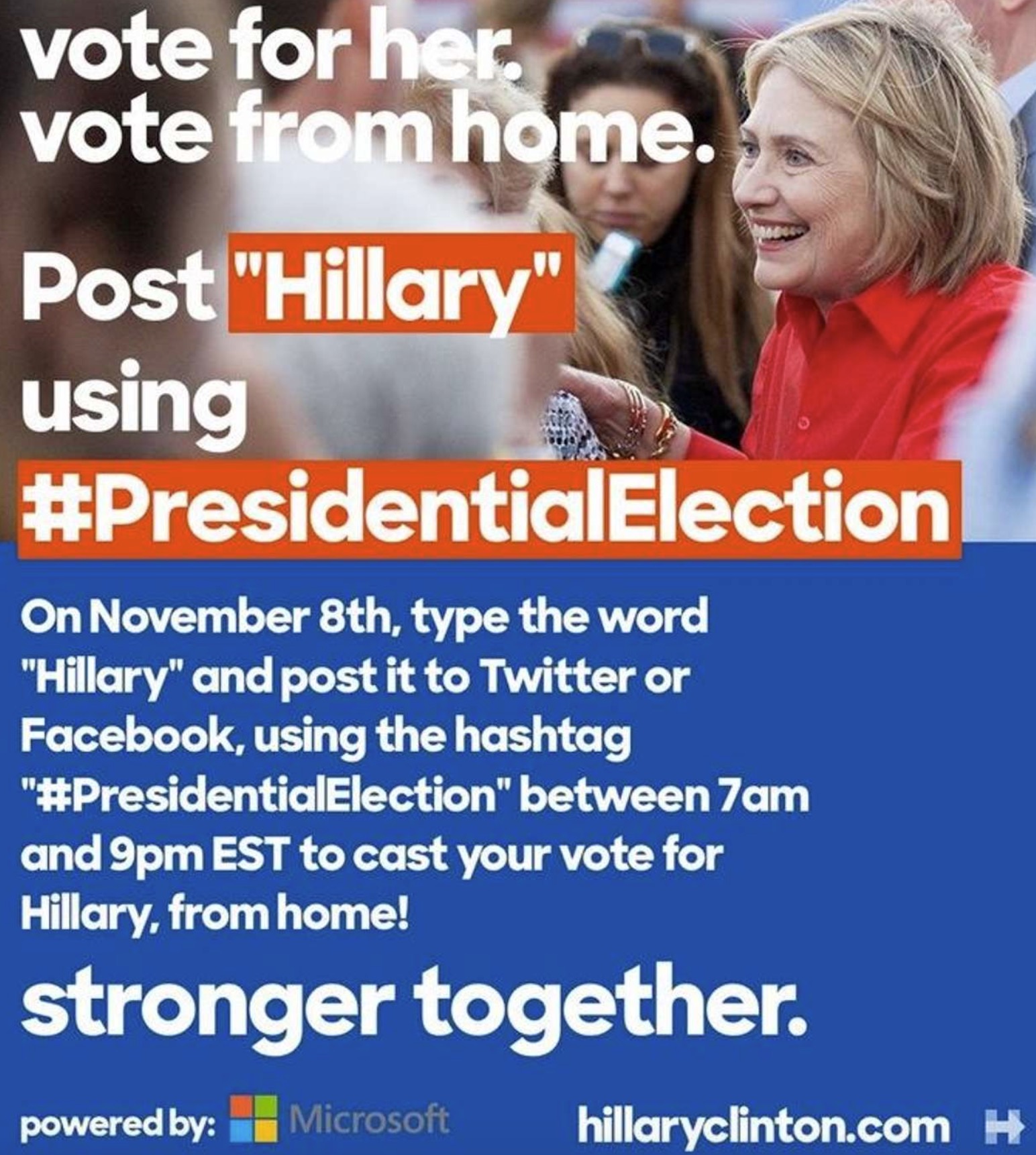

The case against Mackey centers on his efforts to spread fraudulent messages to supporters of the then-Democratic presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton, from September to November 2016.

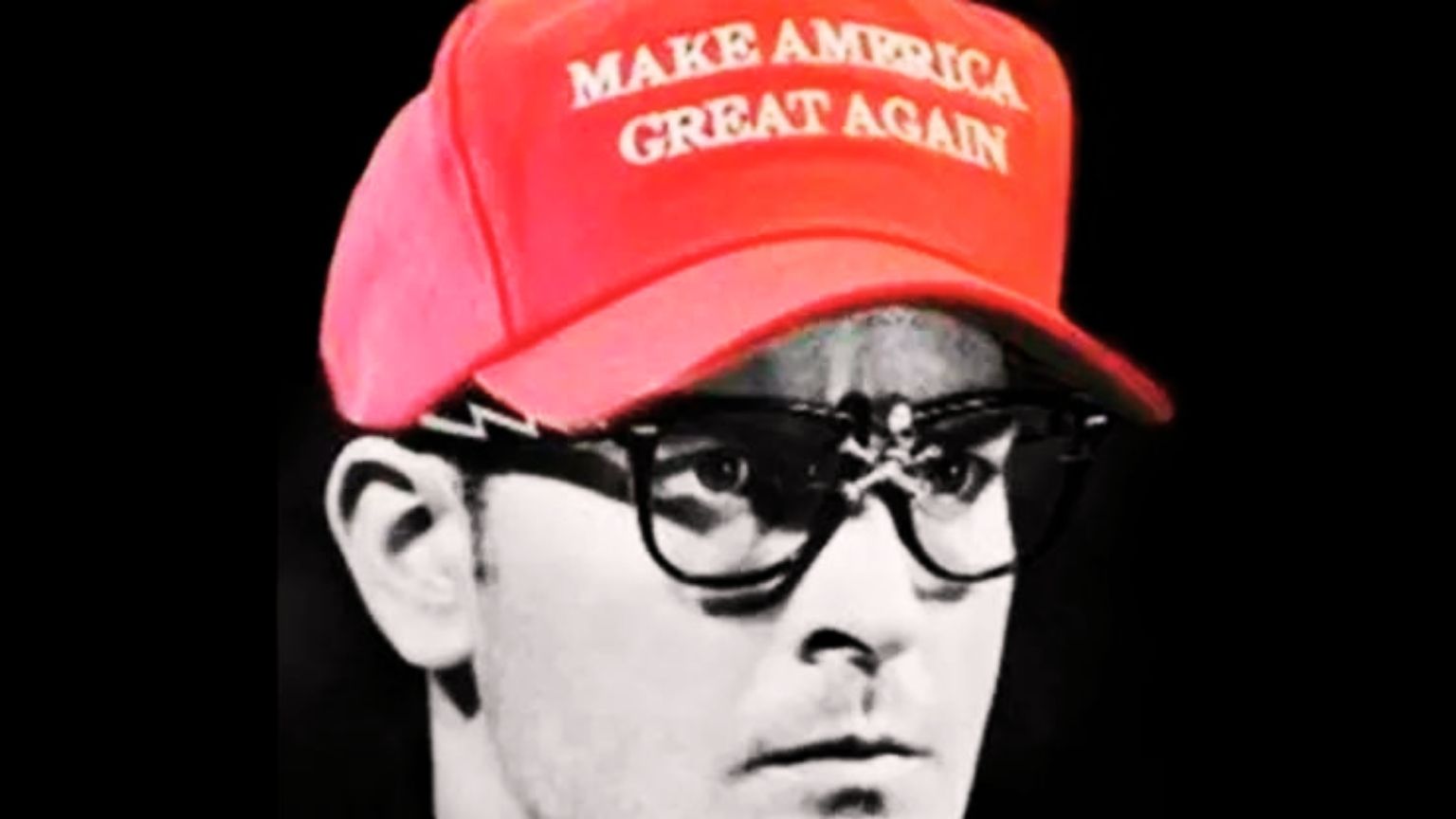

Mackey’s memes encouraged Clinton supporters to “vote” via text message or social media.

One such meme tweet displayed an image of a woman holding a Clinton campaign sign, urging people to “avoid the line” and “vote from home.”

As a result of the memes, prosecutors alleged that at least 4,900 unique phone numbers had texted “Hillary” or a similar message to a designated number.

But the precedent that the court cited were cases involving politicians and election officials and physical acts of voter suppression or direct vote counting – not instances of someone telling lies, through memes or otherwise.

The court acknowledged this, but appears to say it’s irrelevant, saying:

“Defendant Mackey is correct that many–but not all–of the cases above pertain to physical acts such as stuffing a ballot box or counting fraudulent votes. These cases did not, however, rely on the physicality of the acts to reach their holdings. Indeed, many of those cases raised a similar question to the one before the court: whether the statute was ‘sufficiently broad in its scope to include the offense’ charged.

“Foss v. United States., 266 F. 881, 882 (9th Cir. 1920). Not once has a federal court’s response to that question been defined by the offense’s corporeal tangibility. See e.g., Saylor, 322 U.S. at 388 (deciding that the statute included the charged offense based solely because there was a conspiracy “directed at the personal right of the elector to cast his own vote and to have it honestly counted”). Nor does the statute or the case law offer any reason why a court would rely on that fact.”

US Attorney Breon Peace alleged that the jury’s verdict illustrates that Mackey’s “fraudulent” actions were not protected under the First Amendment free speech provisions, and instead constituted criminal behavior.

On the First Amendment point, the court’s ruling was as follows:

“While it is possible that regulation of election misinformation or disinformation could, under other circumstances, be unconstitutional as impermissible proscriptions of political speech, this prosecution targets ‘speech that harms the election process,’ rather than speech about a candidate or a candidate’s views… If Defendant Mackey had tweeted false statements about Hillary Clinton’s policy positions, for instance, a different analysis would be necessary.

“But the issue at bar is whether Tweets telling one candidate’s supporters that they can vote by text or Tweet, therefore making ‘false statements about election procedures, such as the day the election will be held, the proper place to cast one’s vote, or voting requirements’ are proscribable utterances.”