Three of the tech industry’s most recognizable leaders, Mark Zuckerberg of Meta, Evan Spiegel of Snap, and Adam Mosseri of Instagram, will be required to testify in court early next year.

The order came from Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Carolyn Kuhl, who ruled that their participation is essential in a lawsuit alleging that social media platforms were deliberately designed to harm young users’ mental health.

Attorneys for the companies had tried to prevent the CEOs from appearing, arguing that earlier depositions and other executive testimonies already provided sufficient information.

Judge Kuhl disagreed, stating, “The testimony of a CEO is uniquely relevant, as that officer’s knowledge of harms, and failure to take available steps to avoid such harms could establish negligence or ratification of negligent conduct.”

She also noted that their testimony would be “unique,” since the claims center on design features built to “be addictive” and “drive compulsive” use among minors.

Meta argued that compelling both Zuckerberg and Mosseri to testify would disrupt their ability to manage the business and “set a precedent” for future cases. Snap’s lawyers said the decision to call Spiegel to the stand was an “abuse of discretion.”

Judge Kuhl rejected both arguments, saying that those in charge must directly answer questions about their companies’ conduct instead of delegating that responsibility.

After the ruling, Meta declined to comment.

A statement from Snap’s legal representatives at Kirkland & Ellis said the decision “does not bear at all on the validity” of the allegations.

The firm added, “While we believed that the previous hours of deposition testimony and numerous other executives who may testify were sufficient, we look forward to the opportunity to explain why Plaintiffs’ allegations against Snapchat are wrong factually and as a matter of law.”

This case is part of a growing number of lawsuits claiming that social media companies intentionally designed their products to keep young users hooked, resulting in widespread anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues.

New York City recently filed a similar case, accusing several major platforms of worsening the mental health crisis among children.

Lawmakers in Washington have also turned up the pressure. Earlier this year, Zuckerberg and several other tech executives testified at a Senate hearing focused on protecting minors online.

Judge Kuhl’s latest order follows her earlier decision to let hundreds of related cases proceed. She rejected arguments by Meta, Snap, TikTok, and Google that the First Amendment and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act shielded them from responsibility.

Kuhl ruled that these companies cannot rely on federal immunity to block claims about how their products were designed.

While social media sites are not legally considered “products” under traditional product liability law, Kuhl said the negligence theory at the center of the lawsuits “is not barred by federal immunity or by the First Amendment.”

She warned that courts should be careful “not to stretch the immunity provision of Section 230 beyond its plain meaning.”

More than 600 lawsuits have now been consolidated under Judge Kuhl’s supervision in Los Angeles County, including over 350 personal injury cases and 250 suits filed by school districts.

“This decision is an important step forward for the thousands of families we represent whose children have been permanently afflicted with debilitating mental health issues thanks to these social media giants,” the plaintiffs’ co-lead counsel said in a statement back in 2023.

The California proceedings run parallel to a federal case in the Northern District of California, where more than 400 plaintiffs are bringing similar claims. A hearing on the companies’ motions to dismiss that case is scheduled for October 27.

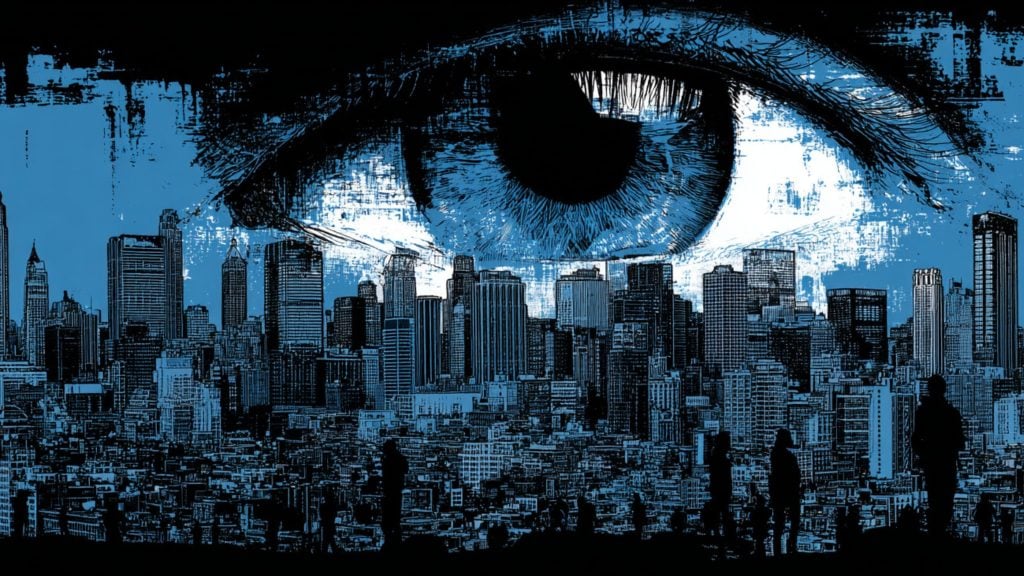

This new wave of litigation against social media companies represents a deeper change in how governments and courts might regulate online expression by going after the algorithms and design systems that amplify speech rather than speech itself.

At first glance, the lawsuits and hearings seem focused on mental health and child safety, not expression or censorship. But the legal and political framing is important.

By targeting “engagement-driven design” and “addictive features,” these cases and proposed laws are implicitly treating the underlying algorithmic systems that determine what speech is seen, promoted, or buried as a form of harm in themselves.

This marks a subtle but profound change: it allows the state to regulate speech indirectly by claiming to regulate “design,” “product features,” or “recommendation architecture.”

If a court or legislature decides that a platform’s recommendation algorithm is “negligent” or “harmful,” that determination inevitably affects what kinds of speech can be distributed or discovered.

Recommendation algorithms are, in essence, systems of speech prioritization, decisions about what messages reach whom, when, and how often. Restricting or reengineering those systems under the banner of safety can therefore function as a form of speech control without ever invoking traditional censorship language.

This distinction between speech and design is legally strategic. US law strongly protects speech, but not necessarily the tools that shape it. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has long shielded platforms from liability for user-generated content, but courts like Judge Kuhl’s are now carving out a space where the “design” of a system can be treated as a separate, actionable product feature.

Once that line is established, governments can begin to compel changes to algorithms, ostensibly for reasons like child safety, misinformation, or mental health, but with broad implications for the flow of political or cultural discourse online.

It’s an elegant censorship workaround: instead of banning or penalizing specific types of speech, regulators can frame their interventions as protecting users from “harmful engagement mechanisms.”

This could pressure companies to downrank controversial content, demote political extremes, or silence fringe voices, while claiming that the target is the algorithm, not the speech itself.