Britain’s speech regulator, Ofcom, has proposed another financial penalty against 4chan under the Online Safety Act, deepening a censorship dispute that stretches from London to Washington.

4chan is an American platform, hosted in the United States, with no presence in Britain. Yet under the Online Safety Act, Ofcom believes that this falls under its authority.

Tensions increased after Ofcom declined to provide 4chan with a copy of its provisional decision before announcing the outcome publicly. According to the platform’s legal team, this decision limited its ability to respond in real time.

Preston Byrne, counsel for 4chan, stated that the regulator’s refusal was intended “to deny us the opportunity for a public rebuttal.”

He further accused the regulator of engaging in “domestic narrative control” by withholding advance access to the decision while preparing to publish its conclusions.

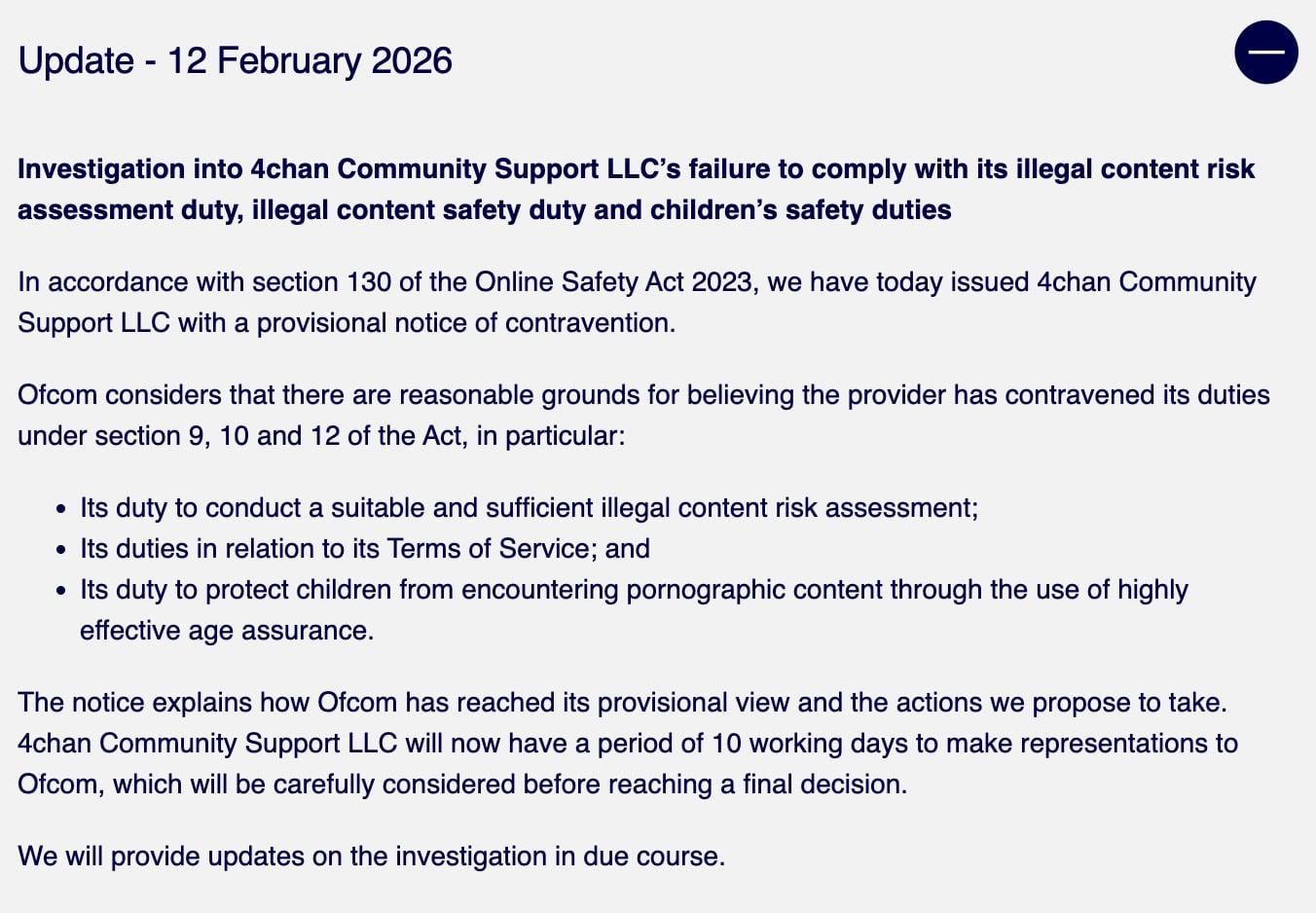

Ofcom announced that it has escalated its enforcement action against 4chan, stating: “In accordance with section 130 of the Online Safety Act 2023, we have today issued 4chan Community Support LLC with a provisional notice of contravention.”

A provisional notice of contravention is a formal step indicating that the regulator believes the company has breached its statutory duties and could face financial penalties if that view is confirmed.

Ofcom said it has “reasonable grounds for believing the provider has contravened its duties under sections 9, 10 and 12 of the Act,” citing concerns about illegal content risk assessments, transparency in its Terms of Service, and the protection of minors.

In particular, the regulator argues that the platform must implement effective age verification measures. For an anonymous, free speech platform, this is obviously a non-starter.

In a sharply worded reply to Ofcom, Byrne rejected the regulator’s escalation outright, writing: “Increasing the size of a censorship fine does not cure its legal invalidity in the United States.” He continued: “After an entire year of your agency’s spectacular failure to get the memo, my only suggestion is that you take a first-year course on U.S. constitutional law.”

The original demand, dispatched in 2025, required 4chan to open its books and explain how it polices its corners of the internet. Ofcom wanted a detailed account of moderation practices and internal compliance material.

According to 4chan’s legal team, the answer was a firm constitutional no. The request, they argue, collides with the First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments. The platform says it cannot be compelled to justify its editorial decisions to a foreign regulator, cannot be forced to surrender internal documents without a warrant issued under US law, and cannot be required to provide statements that might later be used against it.

Those claims now sit before the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, where 4chan is seeking a declaration that Ofcom’s directives carry no binding force on American soil.

Despite that pending lawsuit, Ofcom has revived its August demand in its latest notice. The regulator proposes penalties not only for the earlier refusal but also for failing to spell out in 4chan’s Terms of Service how users are protected from “illegal content.”

Under UK law, that category sweeps in certain forms of speech that remain constitutionally protected in the United States, including material that may be labeled “grossly offensive” or politically controversial. The UK has no such free speech protections.

4chan’s position is blunt: the First Amendment does not allow the US government, much less a foreign agency, to compel it to describe how it will conform to another country’s speech code, or to reengineer an American platform to satisfy overseas standards.

Age verification has become the sharpest point of friction. Ofcom says 4chan has failed to install “highly effective age assurance” measures to shield minors from regulated material. 4chan counters that it operates as an anonymous message board and that anonymity itself is protected expressive conduct under US law.

Forcing the site to collect identifying information from users would amount to compelled de-anonymization.

The enforcement mechanics only add to the tension. Ofcom’s notices have been transmitted by email, a modern version of the imperial telegram. Yet under long-standing principles of private international law, a foreign regulator cannot enforce its administrative orders in another country without first seeking recognition through that country’s courts.

4chan’s counsel says Ofcom has been told repeatedly that if it wants compliance from an American company operating in America, it must obtain authorization from an American judge. That step has not been taken.

When 4chan filed suit in Washington seeking declaratory relief, Ofcom responded by invoking the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, asserting that it is immune from being brought before a US court.

Ofcom did not appear to notice the hypocrisy. The result is a striking imbalance: the regulator claims authority to direct compliance measures at an American entity, yet asserts immunity when asked to defend that authority in an American courtroom.

There is an upside to Ofcom’s overreach, though. If London believed it could extend its regulatory reach across the Atlantic without consequence, Washington is now making clear that the Atlantic works both ways.

The posture has drawn notice on Capitol Hill, where considerations under somewhat of a federal GRANITE Act would adjust sovereign immunity rules in cases involving alleged foreign censorship of Americans.

While constitutional protections cover it, American officials are preparing legislation designed to explicitly block foreign governments from exporting their online speech restrictions into the United States and to give targeted platforms and citizens recourse.

Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy Sarah Rogers confirmed that a new “censorship shield law” is being drafted to ensure that statutes such as Britain’s Online Safety Act or the European Union’s Digital Services Act cannot be used to censor US citizens or companies on American soil.

Rogers said she expects “some kind of shield legislation” to be tabled soon, adding that any attempt to apply these overseas statutes in the United States runs counter to the country’s founding legal principles.